In many ways, WWI was a harbinger of things to come, from the introduction of what we now consider modern weapons and mechanized armies to the use of submarines in an attempt to strangle the lifeblood of a nation, all of it dates from the 1914-1918 conflict.

During the First World war, there were not nearly as many ships sunk off the coast of North Carolina as WWII, but it was still a dangerous place.

The most famous attack of that time was August 16 when the Mirlo sank beneath the waves. The rescue of the crew by men of the Chicamacomico Lifesaving Station is considered one of the most heroic feats of ocean rescue that has ever occurred.

But just 10 days before that, a German U-boat sank two ships at Cape Hatteras in full daylight.

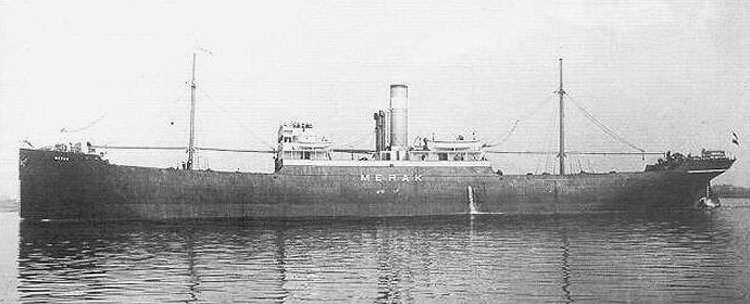

The SS Merak was owned by a Dutch company until early 1918 when US authorities seized the ship and pressed it into American duty. In August of that year, it was steaming south from Newport News loaded with coal.

Sometime on the morning of August 6, U-140 under the command of Commander Waldemar Kophamel spotted the freighter and surfaced hoping to destroy the ship with its deck guns. As the guns opened fire, Captain Charles Gerlach onboard the Merak poured on the speed and he put the ship through a series of zigzag maneuvers.

It seems the evasive action worked. Although the German vessel fired some 30 shells, nothing struck the Merak.

Or it would have worked if the Merak had not run aground on Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras.

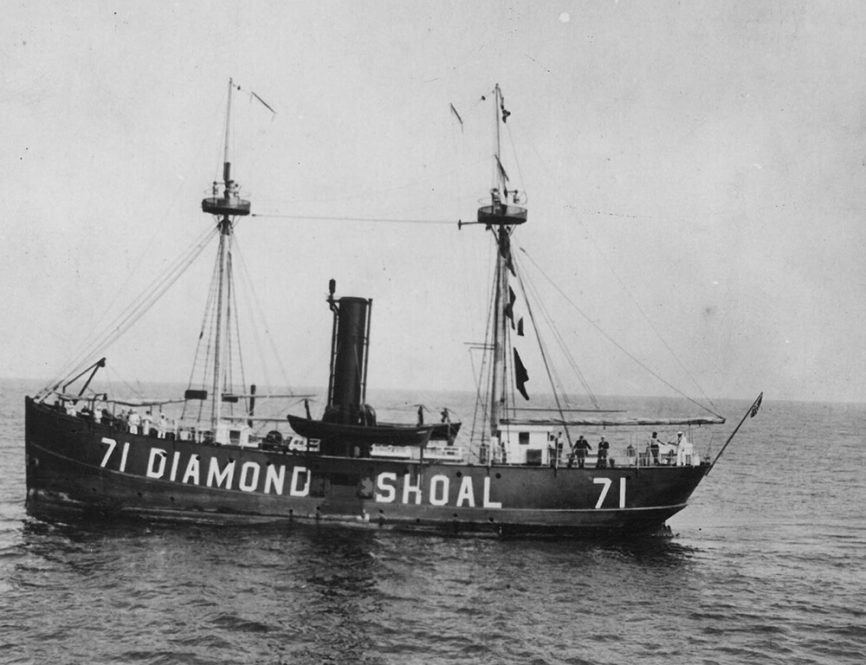

The crew of the Diamond Shoals Lightship LV71, hearing the gunfire and seeing what was happening, began frantically transmitting a warning to all ships in the area that a U-Boat was attacking a ship.

Lightship vessels were floating lighthouses that warned ships away from particularly dangerous parts of the shoreline. Although they could move under their own power, they were very slow and clumsy. LV71 had been on station for 20 years and even if they wished to flee, weighing anchor would have taken over five hours.

Knowing that the Merak was hard aground and hearing the signals from LV71, Commander Kophamel turned on the lightship. A stationary target, the German gunners could hardly miss her and one of the first shots took out the radio tower. Another landed close to the ship. It may have been possible that the near-miss was the equivalent of a shot across the bow, a traditional means at sea to signal an adversary to surrender against insurmountable odds.

LV71 was unarmed and Master Walter Barnett knew if he did not abandon his command, all would be lost. He ordered his 12 man crew into the station’s lifeboat at 2:30 in the afternoon.

Paddling for seven hours they made landfall at 9:30 that evening.

U-140 now headed back to the Merak. The 43 man crew had abandoned ship and with no possible opposition, Commander Kophamel ordered his crew to board the ship and place explosives to sink her.

After placing the charges, the submarine approached the 43 crewmen in the lifeboats, questioned them about the name of the ship, its route, and cargo. The U-140 officers then told the Merak crew which direction to go to get to land and that they should have no problem making landfall before night fell.

They then went back to the Marek, blew the changes and the ship sank quickly.

The Monitor National Marine Sanctuary believes the wreck resting in 135’ of water off Cape Hatteras is the Merak, although there is another ship that was sunk in WWII at about the same location.

That ship, the SS Olympic had about the same dimensions another were other similarities. There are, however, design features that marine archeologists have identified that lead them to believe the wreck is the Merak.

The ship sank with its hull up and there is no access to its cargo holds. If there was a way into the ship, and it could be shown the cargo was coal, it would lay to rest any questions about the ship’s identity.