History is often about chance encounters and opportunities seized, and if ever that was the case, the friendship that grew between William Tate and Wilbur and Orville Wright illustrates that. Well, Bill Tate and to a significant degree, his wife, Addie.

The friendship began with a letter from Tate to the Wright Brothers in 1900. The Wrights, meticulous in their research, combed US Weather Service reports for the windiest places in the country. One of those locations was Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, an area that at that time included what is now Kill Devil Hills.

They sent a letter to Joseph (J.J.) Dosher, who staffed the Kitty Hawk weather station, and he responded with a letter that was friendly and informative, but the important letter came from Tate.

“Mr. J.J. Dosher of the Weather Bureau here has asked me to answer your letter to him relative to the fitness of Kitty Hawk as a place to practice or experiment with a flying machine, etc-. This in my opinion would be a fine place; our winds are always steady-. If you decide to try your machine here & come, I will take pleasure in doing all I can for your convenience & success & pleasure, & I assure you you will find a hospitable people when you come among us.

Signed,

William Tate”

The Wright Brothers moved quickly after receiving the letter. The letter was sent in August. On September 11, Wilbur showed up unannounced on the Tate’s doorstep, following a two-day journey from Elizabeth City to Kitty Hawk across the Albemarle Sound.

In describing the skiff that sailed from Elizabeth City, Wilbur wrote his brother and sister Katharine that, “The sails were rotten, the ropes badly worn and the rudderpost half rotted off, and the cabin so dirty and vermin-infested that I kept out of it from first to last.”

Sailing through a gale, the boat almost sunk, with waves breaking over the boat, soaking everyone onboard. Wilbur noted the effect on the skipper Israel Perry, writing “Israel had been so long a stranger to the touch of water upon his skin that it affected him very much.”

When he showed up on the Tate’s doorstep the only thing he had eaten for two days was some preserves that he carried with him, reasoning that he could not trust any food prepared on the vermin filled, filthy skiff.

The Tates immediately fed him—ham and eggs according to Tate’s recollection—and then came the surprise. Wilbur asked if he could board with the family.

That was a problem. There were four Tates, Bill and Addie, and daughters, Irene and Pauline, in a two-bedroom house. And, evidently, Addie had some real concerns about whether the austere living conditions of the her household would be too plain for what was clearly a sophisticated man of the city.

The walls were thin, and Wilbur could hear the conversation. Going to the door, he told the couple, according to Bill Tate, “I should not expect you to revolutionize your domestic system to suit me.” Then added another sentence indicating he was willing to “subordinate” himself to their lifestyle.

When it was clear the Tates did not understand what he was saying, he simplified it. “I will live as you live,” he told them.

It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the Wrights and the Tates.

Even if Tate couldn’t quite make out what Wilbur was telling him in two convoluted sentences, he was a sophisticated and very well-informed man of his time—especially by the standards of the Outer Banks.

In 1900, Kitty Hawk was part of Currituck County, and Tate was the County Commissioner for the township. It was not until 1919 that the town became part of Dare County.

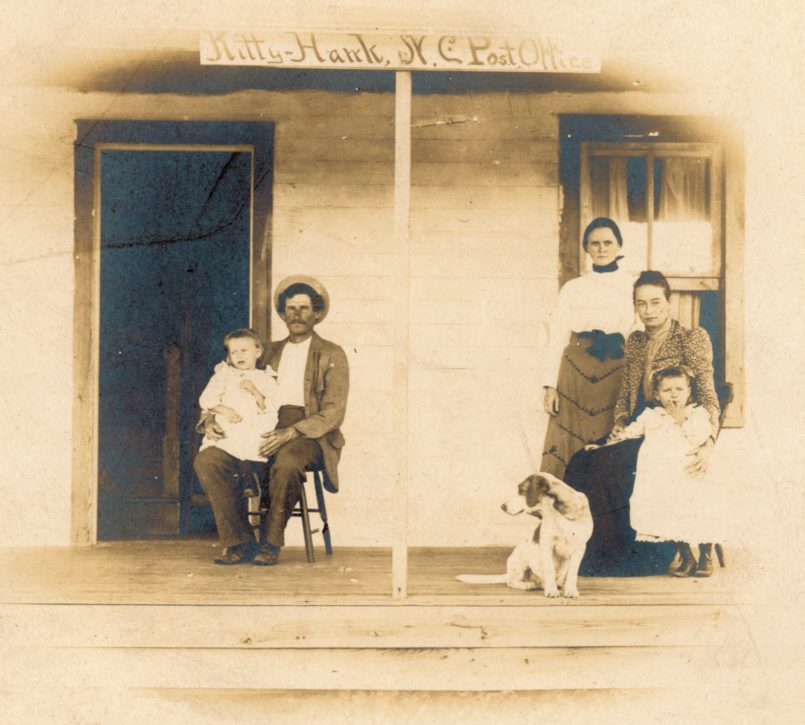

According to Orville, though, he was more than that, the Wright brother describing Tate at one point as “postmaster, farmer, fisherman, and political boss of Kitty Hawk.”

It’s not certain why Tate was able to interact with the Wright Brothers as well as he did, but certainly his education and background seem to have played a role. He was significantly more educated than almost all of his neighbors, having spent at least two years at a secondary school in Elizabeth City.

He was widely read—in fact, one of the reasons he wanted the Wright Brothers to come to Kitty Hawk, was because he knew there was considerable experimentation in trying to create aircraft capable of flight.

Because he had spent time in Elizabeth City, he was also comfortable in a more urban environment. It was largely through his efforts that the wood and materials needed for the more permanent sites the Wright Brothers built for their 1901-1903 visits to the Outer Banks.

Tate was more than the Wright Brothers’ friend—which he was. He was a very successful person in general.

In 1915 he was appointed the North Landing Lighthouse Keeper. Located on North River in Currituck County, the lighthouse was just one small part of Tate’s responsibilities. He was also responsible for keeping a string of 42 beacon lights stretching over 65 miles of waterway lit.

He was very good at his job, frequently cited for the caliber of his work—complemented so often that Coast Guard Historian Dr. Robert Browning took note writing, “It is truly amazing that any one man would be cited so many times.”

And Tate was somewhat visionary. In 1920 he became the first active member of the US Coast Guard to use an aircraft for an inspection. After landing he wrote, “This keeper made the trip along the river in an airplane, flying, about on a level with the lights and within 50 feet of the same, and it was easily seen whether they were burning.”

It was his lifelong friendship with the Wright Brothers, though, that William Tate is most remembered for. At one point in time, when their flights at Kitty Hawk were being overlooked, even ignored, and Tate’s advocacy for that first flight at Kitty Hawk eventually led to the construction of the Wright Brothers Memorial in Kill Devil Hills.

He also, in 1928, worked with the town of Kitty Hawk to create the first monument to the Wright Brothers achievement…a stone obelisk at the location of what was once his home on Moor Shore Road. The monument remains standing to this day.