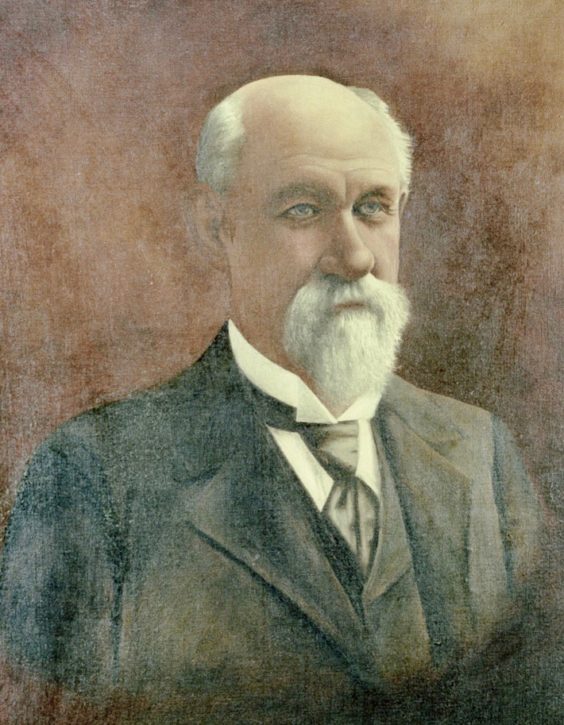

Thomas Jarvis

Governor, Ambassador, but a Mixed Legacy

Jarvisburg never was much of a town. If it has a claim to fame it’s the home of the original Cotton Gin retail store and Sanctuary Vineyards.

But at least one of its sons rose to heights that very few people ever achieve and his name and achievements are called out in a faded highway sign across US158 from the Cotton Gin.

Thomas Jarvis was born in 1836 in what is now Jarvisburg. The son of Elizabeth and Bannister Jarvis, a Methodist minister and farmer, the Jarvis family roots ran deep in North Carolina, the name appearing in official records as early as the 1690s.

It is apparent, though, that by the time Thomas was born the Jarvis family was not wealthy, although they could certainly provide for their son’s needs as well as his brother and three sisters.

In 1856 he enrolled in Randolph-Macon College. With no money for tuition, he worked summers as a teacher to pay for his education. Graduating in 1860, he continued on receiving a Master of Arts the following year.

When the Civil War erupted, he enlisted with the CSA as a Lieutenant with the Eighth North Carolina Regiment. His military career ended when he was wounded in the right arm during the Battle of Drewery’s Bluff in May 1864. He was a captain at the time.

Returning to Jarvisburg, he took the first steps in a political career that would lead to the Governor’s mansion and beyond. In 1865 he was elected a delegate from Currituck County opposing the writing of a new state constitution. The electorate later voted against the new constitution.

By 1868 he was a lawyer and becoming increasingly involved in state politics for a resurgent Democrat party.

As Jim Crow laws began restricting the ability of persons of color to vote, his Democratic party gained strength and in 1870 they took the house and Jarvis was elected Speaker of the House.

With a growing law practice, he moved to Greenville in 1875, but continued his political career, opposing another new state constitution. Although the constitution passed, he was instrumental in giving the state legislature additional powers.

When Zebulon Vance was elected governor in 1876, Jarvis was his Lieutenant Governor, and when Vance was elected to the Senate two years later he became governor.

Consistent with his time in the state legislature, he was a fiscal conservative, railing against government extravagance and corruption. He sold state holdings that were costing the state money, including a North Carolina owned railroad. Although a fiscal conservative, he helped to create a statewide mental health system and teacher’s colleges—called normal schools at the time.

Elected to a full term as Governor in 1880 he continued to champion education and pushed to codify the state’s laws.

At the end of his term as governor in 1884, President Cleveland appointed him ambassador to Brazil, although there is reason to believe he was hoping for a cabinet position. When Cleveland failed to win reelection in 1888, Jarvis resigned his ambassadorship and returned to North Carolina.

Until he passed away in 1915 Jarvis grew his law practice, worked to unite the national Democratic party and championed education. In 1907 he and a friend, William Ragsdale, wrote the enabling legislation for a teachers’ training school in Greenville.

Jarvis went on to serve as the chair of the Building Committee of East Carolina College—today ECU.

Although there is much about Jarvis that shows a forward thinking politician, his legacy is mixed. There is considerable evidence that he was instrumental in creating the political atmosphere that led to the Wilmington, NC race riots of 1898—riots that led to the death of Black residents and the resigning under duress of the city’s elected officials, all of whom were Black.

The perpetrators of the violence were exclusively white, led by former CSA officers. There was no investigation, and no one was ever charged.

It is apparent that Jarvis, as was typical for a southern white politician of the time, believed in separate educational facilities for the races, yet his view of education for all North Carolina residents clearly included people of color. Under his guidance, the state invested in Black schools and colleges.

He also carried on a regular correspondence with Booker T. Washington and hoped to bring him to the state to address one of the Colored Normal schools he championed.