Looking out on the Pamlico Sound from the Salvo Day Use Area just south of the Tri Villages on Hatteras Island, it may be hard to imagine that 162 years ago, some of the first battles of the Civil War were fought on the Outer Banks. In fact, the battles were very real, and although the Outer Banks does not figure prominently in the histories of the conflict, the battles that were waged here had an outsized impact on the war.

It was on the Outer Banks that the first significant Union victories of the war happened, and although ultimately the campaign was a lopsided victory for the northern forces, there were missteps along the way.

Perhaps no incident describes those missteps as well as the capture by Confederate forces of the gunboat USS Fanny.

The Fanny should never have been where she was on October 1, 1861. A converted tugboat, the ship was lightly armed, and her crew poorly trained.

What brought the Fanny to the waters of Pamlico Sound off the Salvo beach was a series of events that began with the capture of Hatteras and Ocracoke Inlets by Union forces in September 1861.

Anxious to support a local population with strong Unionist leanings, Colonel Rush Hawkins, who was in charge of the Union forces at Hatteras, dispatched newly arrived troops of the 20th Indiana infantry to what is now the Tri-Villages area or Chicamacomico as it was called at that time.

It can be argued what Hawkins was doing was strategically a good move. Confederate forces had been steadily strengthening their position on Roanoke Island and had moved troops to Nags Head on the Outer Banks. A strong Union presence close to Roanoke Island could potentially check any movement the Confederates were planning.

But if the strategy was sound, the execution was not.

Arriving at Chicamacomico, the 20th Indiana was short on ammunition, artillery, and food. And it does not appear as though Col. Hawkins had made plans to support them with more personnel and equipment.

Even if Hawkins did intend to quickly resupply the 20th Indiana, it is not at all clear if he could have done so. Although he told Col. Brown, commander of the Indiana regiment, he would be resupplied quickly, Hawkins had very little to send. Much of the ammunition the Union forces brought with them had become waterlogged in the assault on Fort Hatteras and was unusable. Although he promised additional artillery, researchers are in agreement that, at most, there were two pieces of artillery that could have been sent—hardly enough to help.

Nonetheless, it was clear that the 20th Indiana position could not be held without more supplies. The troops, though, were camped beside a relatively shallow area of Pamlico Sound, and the only boat available that had any hope of getting close enough to shore to offload supplies was the USS Fanny—the converted tugboat.

Early in the morning of October 1, the Fanny was loaded with food, ammunition, and other supplies and began the journey north from Hatteras to Chicamacomico. There is uncertainty about how well-armed the tugboat was, but all accounts agree the boat had insufficient artillery on board to repel any serious attack. Exacerbating the situation, the crew was mostly Army personnel who were unfamiliar with firing weapons from a boat.

Making matters worse, the Fanny was ordered to rendezvous with the USS General Putnam, which was patrolling The Croatan Sound off Roanoke Island, and transfer one of its guns to the Putnam. After receiving the gun, the Putnam left to resume its patrol duties.

Some sources site orders that the Putnam’s commander, Master Hotchkiss, was supposed to remain with the Fanny as she offloaded her supplies. There is not, however, complete agreement on that point.

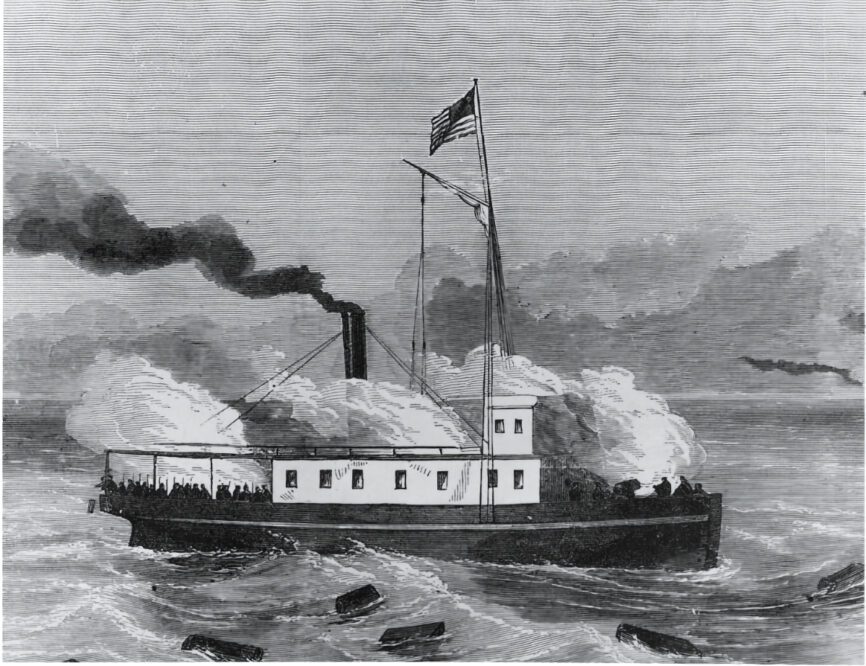

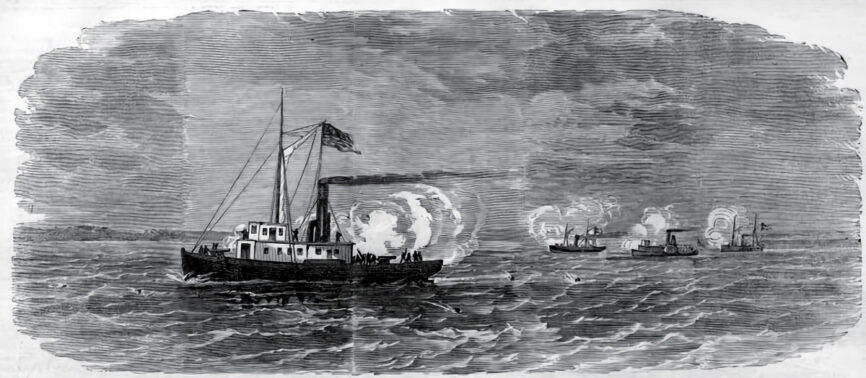

At about 1:00 in the afternoon, the Fanny arrived at Chicamacomico, anchoring about three miles offshore, and prepared to offload supplies. It does seem that the first of the supplies had been unloaded, but before the bulk of supplies could be moved off the boat, at about 4:00 in the afternoon, three Confederate warships, the CSS Curlew, Raleigh, and Junaluska under the command of Captain William Lynch, sailing from Roanoke Island, steered directly at the Fanny and opened fire.

The Fanny returned fire and shipped its anchor, hoping to slip around the oncoming Confederate boats. Its only escape route was to stay as close to shore as possible, and it ran aground.

Outgunned and unable to maneuver, the USS Fanny had no choice and surrendered to the Confederate fleet late in the afternoon. Around 40 prisoners were taken—there is some ambiguity on that—along with most of the supplies, which the Confederates desperately needed. And, of course, the USS Fanny, which was promptly recommissioned the CSS Fanny.

Coming on the heels of the loss of Hatteras and Ocracoke Inlets, the capture of the Fanny was hailed in the Southern press as a decisive victory. “Another Handsome Achievement” the headline in the October 9 Richmond Enquirer read.

A handsome achievement perhaps, but ultimately it had little effect on the outcome of General Ambrose Burnside’s campaign to retake the interior waterways of North Carolina. The Union forces were simply too well-supplied and had superior weaponry. That was particularly evident when in February of 1862, the Union Navy, now fully integrated into Burnside’s plans, overwhelmed the mosquito fleet, as the CSS fleet was named and paved the way for the capture of Roanoke Island on February 7.