Shipwreck Mystery Solved

Taking the form of mystery novel, a team of marine scientists at the Coastal Studies Institute on Roanoke Island appear to have solved the riddle of the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck in the waters off Rodanthe on the Southern Outer Banks.

The site is marked by a rapidly deteriorating metal shape, and it’s not an old wreck. Yet as Dr. Nathan Richards, head of Marine Archeology for CSI explained, even though the wreck seemed relatively recent, there did not seem to be very much information on it.

The search for the true identity of the ship began almost by accident in 2010 when Richards and a group of interns were unable to dive the Oriental, a Civil War shipwreck off Pea Island because of sea and weather conditions.

Plan B was to look at navigation charts of Pamlico Sound, locate a marked shipwreck and investigate.The team drove to the end of Pappy’s Lane, went out to the wreck and started taking measurements. After examining the wreck, the team talked to residents.

“We found a whole lot of stories about this wreck,” Richards said. “The prominent one was that it was gravel barge. However, there’s a problem with that story. It doesn’t look like a barge.”

“The implication is that it could still be a barge, but it probably was not built as a barge but was converted to a barge,” he explained. “I felt there was a layer of history here that had been forgotten.

Four years later Richards was working with NCDOT examining an area that the state was planning on dredging for the Rodanthe emergency ferry. There was nothing much of historic significance in the dredge area.

The wreck was on the edge of the exam area, and as Richards remarked, “After surveying the seabed and finding nothing for a long time, I was about ready to do something like solving a mystery of an abandoned barge.”

He and his team started researching the wreck, hoping to determine the story of the ship. Everything seemed to lead to a dead end.

“We went down all kinds of paths for all kinds of vessels,” Richards said. “One particular lead was we had these steel ocean going barges from the Panama Canal project…but once we got the blueprints they didn’t line up.”

Then came a break.

Richards was given some images from an unrelated project that showed the ship off Pappy’s Lane in the 1970s before it had deteriorated to a rusted hull beneath the water. The image was filled with information that could be used to identify the ship. A high image scan was created and new research began.

This time the the focus was on a late 19th century or early 20th century Coast Guard buoy or lighthouse tender.

“There were number of them that were missing. That no one had counted for in the historic record,” Richards said.

As Richards was going down his dead ends, NCDOT was outlining the Bonner Bridge project, including the Jug Handle concept that will bypass the S Curves. The projected route will take the bridge very close to the wreck, and the wreck would be in the construction zone.

Based on that information, the site was noted as having potential as a historic site under the National Register of Historic Places. Again Dr. Richards and his team were working with NCDOT, but this time to specifically examine the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck.

Hoping to determine exactly when the ship sunk, historic navigation charts were examined. The wreck first appears in the charts in 1969.

“That doesn’t mean it first appeared in 1969, but it had to be there in 1969,” Richards said.

Then came additional confirmation. Aerial photographs were examined. “The earliest it appears is in June of 1969,” Richards found.

Checking over photographic records at the Outer Banks History Center from the 1970s additional images were found of the ship still above water and intact, giving the team a fairly “tight window” of time.

By the 1980s images showed a shipwreck that was quickly deteriorating.

“As an archeologist, we’re not dealing with a pristine Pompeii-like encapsulated archeological site,” Richards said.

The team began the work of an onsite excavation, taking careful measurements of what they found. The wreck, resting in 3’ of water was readily accessible, but an entire day in the water made the work difficult. Much too degraded to be moved from the site, targeted excavations of the stern and midsection were used.

“The process is painstaking. By the end of this process we had drawn 177 separate drawings,” Richard said.

The drawings did not match any blueprint of buoy or Lighthouse tenders.

What the detailed excavation of the shipwreck did reveal was a very distinctive stern. The ship had two skegs—fins, on the outside of two tunnels that would have been the housing for two propellers.

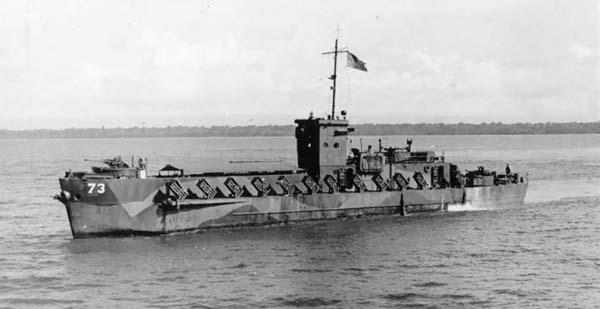

“At this point we know we have some strange function. And what it turns out to be, this is an amphibious landing craft,” Richards said. “These particular craft are very significant in the context of the Second World War, particularly in the context of the American efforts to retake the Pacific.”

Now the archeological detectives had some real information to work with.

But there is more to the story. Richards explains that the first iterations of the landing craft—LCI, Landing Craft Infantry—were largely unarmed. As the Marines discovered at Tarawa, one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific campaign, that lack of armament was a disaster.

Back to the drawing board, the military created a gunboat using the LCI platform. There were some distinctive features on the stern of the now designated LCS, and the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck had every one of them.

Although not yet confirmed, Richards indicated the ship may well have been the USS LCS (L)(3)-123. The L would have meant it was the larger version; the 123, the 123rd of the series built. If Richards’ findings are confirmed, the ship was launched in November of 1944 by George Lawley & Son, the designer of the craft, from their shipyard in Neponset, Massachusetts.

How, then did it end its days as a rusted hulk beneath the waters of Pamlico Sound?

After seeing extensive combat in the Pacific in 1945, USS LCS (L)(3)-123 was sold as surplus in 1947. Purchased for the Hunt Oil Company based in Hampton Roads, the ship was converted to a fuel barge, and plied the waters between Norfolk and the Outer Banks.

It appears as though it ran aground in 1969 pulling two gravel barges off the shoals near Rodanthe. Unable to refloat the ship, the owners salvaged the ship and abandoned it.