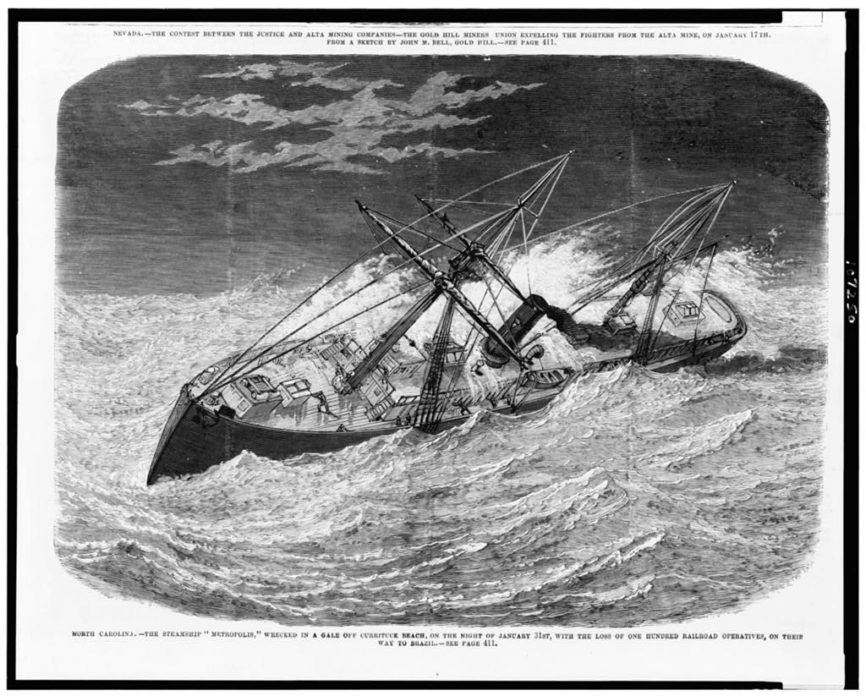

Outer Banks Shipwreck “Metropolis”

She Should Never Have Put to Sea—The Wreck of the Metropolis

The Metropolis should never have been put to sea in January of 1878.

The ship started its life in 1861 as the USS Stars and Stripes, a gunboat and occasional steam powered tug for the Union Army. Its first assignment brought it to the Outer Banks, where it participated in the campaign to wrest control of northeastern North Carolina from Confederate control.

After the war, it was sold as surplus and began a new life as a commercial steamer. For the next six years, she plied the waters of the East Coast until she was sold to the Lunt Brothers, an East Coast shipping company.

But the Stars and Stripes at 150’ and 409 tons was too small for the new owners, and the ship was cut in half, and 56’ additional hull was added. The US Treasury Department—which was responsible for maritime safety at that time—was able to establish a “master carpenter” who had overseen the second lengthening of the vessel but could not find a certificate of seaworthiness for it.

For the next seven years, most of the ship’s work was along the Eastern Seaboard and Gulf of Mexico. In January of 1878, however, she was headed for Brazil, loaded with 700 tons of cargo, mostly steel rails, for a jungle railroad. There were also 248 passengers when the Metropolis departed Philadelphia.

There were problems almost immediately. Even in the comparatively calm waters of Delaware Bay, she began taking on water, and when the ship got to the open sea off Cape May, conditions worsened.

Ship Captain Ankers was determined to press on. The seas began to rise as the ship passed Chesapeake. It’s unclear if the seas caused the problem or if the 500 tons of steel rail was improperly loaded, but the cargo shifted, causing some of the ship’s seams to leak.

But Ankers, believing the pumps were strong enough to keep the water at bay, opted to continue steaming south. Sometime during the night, the pumps gave out, and sea water flooded the engine room.

The ship was now at the mercy of wind and wave. The captain did what he could to ride the currents, and when the opportunity came to beach the ship, he steered for the shore, grounding the ship on a sandbar about 100 yards from the Currituck Banks beach and about four miles south of the Jones Hill Lifesaving Station. The time was 6:45 a.m. The date was January 31.

According to the initial investigation of the sinking of the Metropolis by Captain J. K. Merryman of the Revenue Service, the first people on the scene were local residents N.E.K. Jones and James Capps at 8:00 a.m. Capps left to tell a neighbor, S.C. Brock, to ride his horse to the Jones Hill Lifesaving Station at the base of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse and tell the Lifesaving crew what was happening.

Jones started pulling people out of the surf.

Merryman, in his report, notes there is considerable confusion about when the Jones Hill Lifesaving men arrived on scene and when the equipment needed to effect a rescue made it to the beach.

“It seems to be generally conceded, however, that the mortar apparatus was on the ground about noon,” he wrote in his report.

What followed was perhaps the most defining moment of a day of disaster.

The mortar fired a round shot with a heavy line attached to it that would serve as a lifeline between the ship and shore. When secured, a breeches buoy would be sent along the line to bring people safely to shore. Keeper John Chappell only brought enough gunpowder for two charges.

The first shot went long. “The failure of the first shot is not unusual,” Merryman noted.

The second shot was on target, and the line secured. But suddenly, a wave caught the Metropolis, and the ship keeled violently, breaking the line.

Chapel’s failure to bring more charges was perhaps the most critical failure of the day.

Currituck Beach residents who were at the scene offered more powder, but the gunpowder was not the measured amount the Lifesaving Service used, and subsequent attempts were unsuccessful. It is this one failure that Merryman was most critical of, writing, “The line was at once (repaired) on the beach for another attempt, which was for some time delayed by the strange and inexcusable neglect of the keeper in having but two charges of powder in his flask.”

Chapel’s failure to bring an adequate amount of powder led directly to his termination from the Lifesaving Service.

The lifesaving crew had not brought their surf boat with them. According to testimony of the Jones Hill crew, when Brock brought news of the disaster to the station, he was asked if they should bring the boat. He told them he did not think the boat would help as the ship “…was fast breaking up.”

Without their surf boat and unable to send a line to the ship, the Jone Hill Lifesaving crew was still critical to saving lives, Merryman felt.

“The surf by this time was running high, and the waters were laden with floating fragments of the wreck…and driven by the rolling breakers shore-ward, came the struggling, drowning people, to be received in the welcome arms of their rescuers…who strove in their work waist-deep in the inner breakers and undertow,” he wrote, and then lists every member of the Jones Hill station.

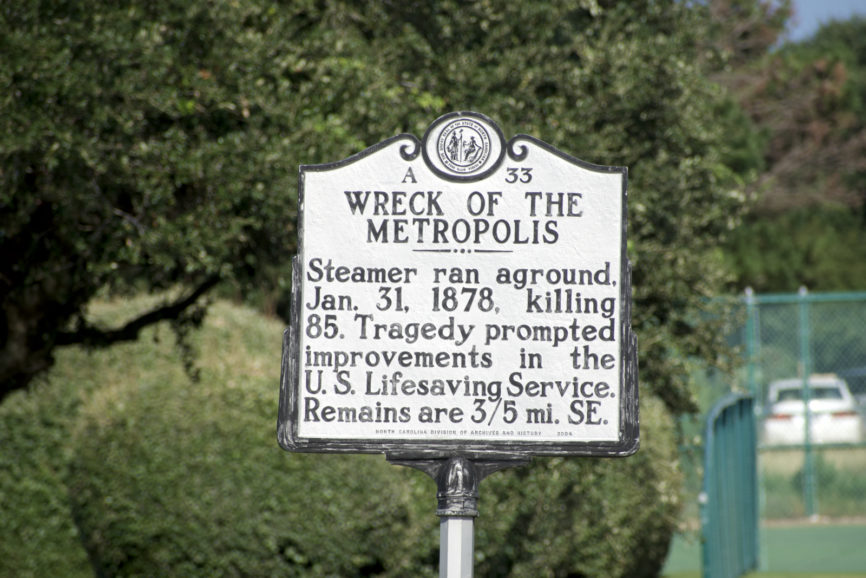

There is some confusion about the exact number of deaths that January night, with figures ranging from 85-102. Regardless it was one of the worst shipwrecks in Outer Banks’ history.

Among those saved were Captain Ankers, but Ankers was bitter in denouncing the Lifesaving Service.

“Had they been properly provided and got there before noon, everyone would have been saved,” he said.

Merryman, although very critical of Keeper Chapel, was much more measured in his criticism of the Lifesaving Service.

He noted, as an example, that a surfman had patrolled the area in the early morning hours before the Metropolis ran aground. Typically when a surfman returned, another would leave on patrol. Under the best of circumstances, that would be approximately 6:30-7:00 a.m. Leaving the station at that time would place the surfman at the Metropolis just about eight in the morning when Jones and Capps first saw the wreck.

Other issues were raised as well in his report. He found that no attempt was made from the Metropolis to send a line to shore when it was apparent the mortar had failed. He further points out that the ship did not carry any of the apparatus needed to signal distress.

“If the Metropolis carried, as I am informed she did not, a small gun or swivel for making sounds of distress, and it had been fired two or three times when she struck or as she neared the land, its report would have been heard at the lighthouse and there would have been time for the life-saving crew to reach the wreck before the hour they were notified by Mr. Brock,” Merryman wrote.

His most critical observations, though, were reserved for the ship itself. After examining the wreckage, he wrote, “…Her rottenness (was) so apparent that there was but one opinion as to her unseaworthiness among the many persons I met on the ground.”

Coupled with the USS Huron disaster just two months earlier, Merryman’s observation that more stations were needed along the Outer Banks was well-received in Congress.

“The necessity for additional stations along this coast is apparent from the length of the patrol alone,” he wrote.

Congress agreed and, although bitterly divided along partisan lines at that time, came together to provide funds to build additional stations and hire the crews to man them.