All quotes taken from Record of proceedings of a court of inquiry, convened by the Secretary of the Navy, Wednesday, December 5, 1877.

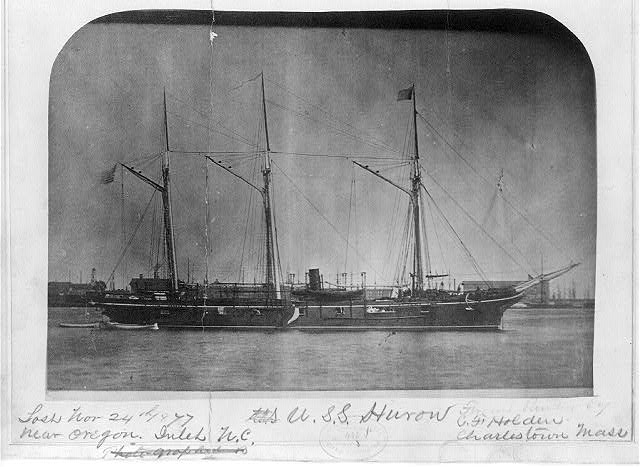

The USS Huron was one of the last of her kind. She was an iron-hulled steamer, fitted with three masts for sail power if her engines failed. The Huron and two sister ships were the last iron-hulled ships the US Navy built; everything afterward was steel-hulled.

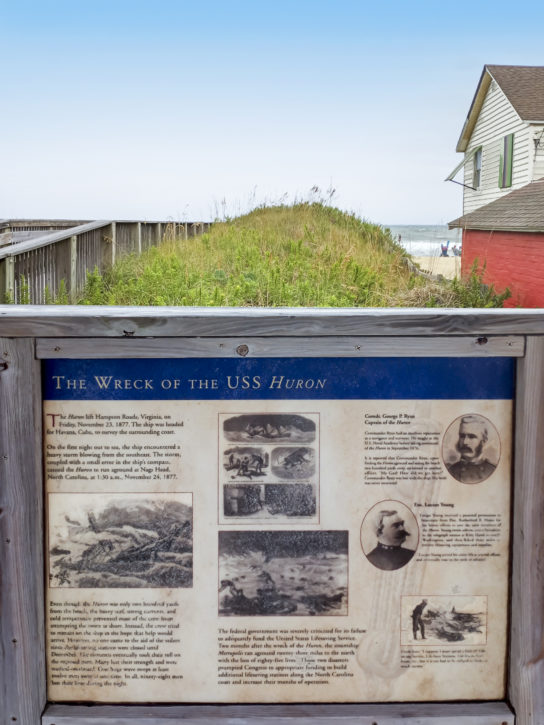

Commissioned at the Philadelphia Naval Yard in 1875, the Huron sailed the Caribbean for two years before heading for maintenance and repairs at the New York Naval base in June of 1877. Repairs completed, she returned to her home base of Norfolk. On November 23 the Huron set sail for a mapping expedition of Cuba under the command of Commander George P. Ryan. With a wide range of experience on a number of ships, Ryan was considered an excellent officer.

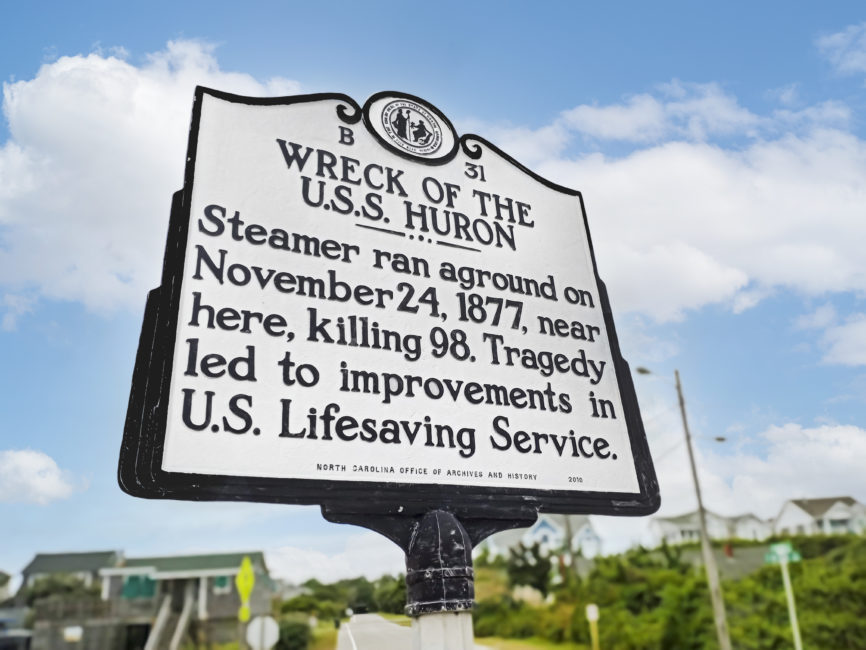

The Huron never made it Cuba, sinking just off the Nags Head shore in one of the most horrific shipwrecks in the history of the Outer Banks.

It was a tragedy that did not have to happen. Inadequate funding from Congress had forced the Lifesaving Service, the predecessor to the US Coast Guard, to open their stations seasonally. The Nags Head Lifesaving Station, just three miles from the site of the disaster, was closed as the crew of the ship were battered by waves and drowned. In the end, 98 crewmen perished. Just 34 survived.

When the Huron left Norfolk the weather was cloudy and misty with a light wind according to the testimony of the survivors. As day gave way to evening, wind and rain picked up and the seas were running heavy, but to a man, they felt the Huron was in no danger.

Commander Ryan steamed south on a heading that would keep them between the shore and the Gulf Stream.. According to testimony from Master William Conway at the Court of Inquiry in December of 1877, Commander Ryan wanted to avoid the Gulf Stream, although it was not clear why that was the case.

Whatever the reason, at 1:30 a.m. on November 24, 1877 the USS Huron struck a sandbar just 200-250 yards off the Nags Head beach.

When he realized they were on a sandbar just off Nags Head, Conway reported Commander Ryan as saying, “My God! How did we get here!”

What followed were eight hours of sheer terror.

The ship, Conway testified, was “… inclining about 40°.”

The engines had steam pressure, but the attempts to back it off the reef were unsuccessful and it was just a matter of time before water pouring in from an unsecured hatch would force the engines to stop. The hatch over the engine room could not be sealed, Assistant-Engineer R. G. Denig reported.

“It was then impossible to batten down the engine-room hatch because the main guff and main trysail had fallen over it,” he said.

At first, there was hope of rescue Conway said. “No one thought we should lose our lives, but that the ship would be lost and that at daybreak we should all get off.”

The engines failed at 2:15 a.m. but the distress whistle that worked off the steam pressure from the engines continued to sound for some time Denig told the court of inquiry.

“The whistle was blown as a signal of distress, and it continued to blow till some time after I had left the engine-room, and probably until all the steam was out of the boiler,” Denig said.

The whistle was but one desperate signal for aid. Common signals for a ship in distress at that time were rockets and burning lights.

“I burned over a hundred lights and sent up five rockets…” Ensign Lucien Young recalled.

But as the night went on, the plight of the Huron became ever more desperate. The ship keeled ever farther over and by daylight, the waves were breaking over the ship, and the full horror of the ship’s plight began to emerge.

“Just before daylight the men began to be swept from the forecastle,” Conway said.

An attempt to put a lifeboat in the water failed, Denig recalled. “There were in the launch with several men and Commander Ryan…when she was carried away. I saw her stove. She fell stern first and hung by one davit at the other end, to which davit two men clung until they were drowned.”

Conway, exhausted and unable to cling to the rigging any longer, decided to swim for shore in the morning light.

“I could not hold on much longer, I allowed myself to be washed off and swam ashore. …I was about five minutes in the water, and then struck the beach and was hauled out by some fishermen, two of whom carried me, holding by each arm, up to a hut,” he said.

Stripped naked by the sea, Conway was given clothes by the fishermen.

Denig climbed into the mizzen rigging and at 9:00 a.m. knew he had to swim ashore or die.

“When I left the ship, the poop-deck and cabin were completely washed away…The main-mast and mizzen-mast, the smoke-stack, and the starboard gun were still in place. A few moments after I reached the shore the main and mizzen masts and the smoke-stack were gone,” he told the court of inquiry.

Ensign Young had already made it to shore and that is when the full horror of what was happening became apparent. The Nags Head Lifesaving Station with all the equipment needed just three miles away from the wreck.

“I asked the fishermen if they had seen our signals. They said, ‘Yes, almost the first one.’ I asked, ‘Why didn’t you get the life-boat?’” he remembered asking.

The station was locked and the fishermen were afraid to break it open he was told.

“Come, and I’ll break it open,” he said.

His leg had been injured, but Young set off down the beach.

“It hurt me fearfully to walk on the sand, but I got there, running and walking, about 9.30 a. m.; found no one there; broke open the station; got out the mortar and lines and powder.”

But by the time he got back to the Huron, it was too late.

“When I got abreast the wreck there was no one on her, and so I did not use the mortar. They patrolled the beach, hauling men out, some alive, some dead. Eight dead were found; and thirty men and four officers, including myself, alive,” he said.

One of the most chilling statements about the horror of that night came from Denig when the Court of Inquiry posed its fifth question for the day on December 7:

“After you came on deck, was any measure possible to save the crew, or was nothing possible?

Answer. Nothing was possible,” reads the court records.

The recently installed telegraph system of the Army’s Signal Service with a station at Kitty Hawk, quickly spread the news of the sinking of the Huron and it was headline news from Portland, Oregon, to Dallas Texas, to New York City. Coupled with the soon to occur disaster of the Metropolis off the Currituck Banks, Congress was spurred to action and finally provided the funds needed for a professional lifesaving service.

No cause of the sinking was ever established, although compass error caused by the iron hull of the ship is a very real possibility in this case.