World War II was a terrifying time along the Outer Banks in 1942. A narrow predictable shipping lane along the coast turned the waters of the Atlantic into a “Torpedo Junction” for German U-boats.

There was little or no protection for the unarmed merchant ships that plied the waters. It took more than four months for regular air patrols searching for submarines to begin. Perhaps even more disturbing, US Navy brass refused to accept the British recommendation that armed convoys could protect shipping, and it wasn’t April that a convoy system was started.

More than 30 ships met their fate at the hands of the U-boats in a three month period before more aggressive action from the allies came to their aid.

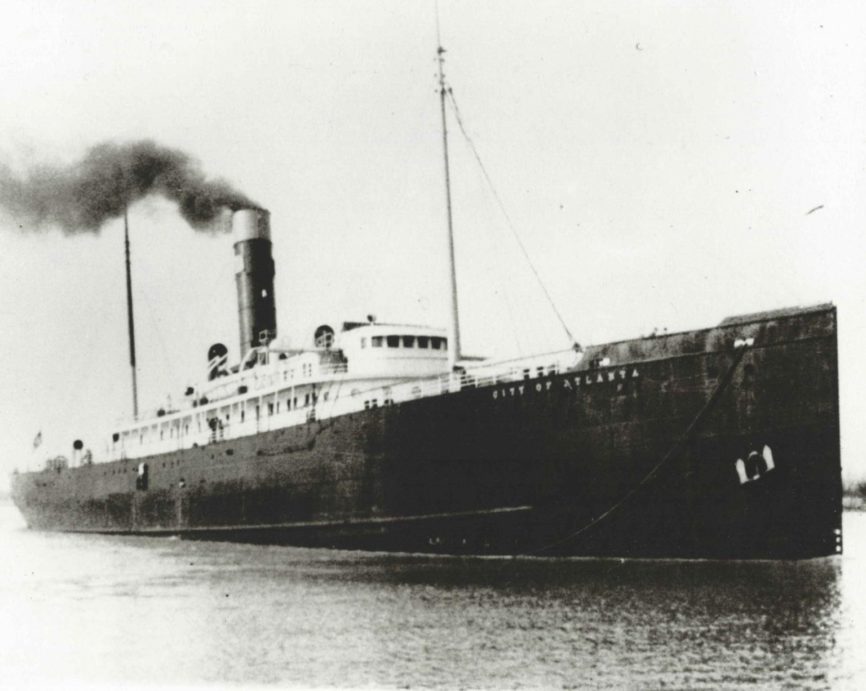

One of the most horrific and tragic stories is the sinking of the City of Atlanta.

In mid-January, she departed New York City en route to her homeport of Savannah, Georgia. There were a few passengers among the 46 aboard her, but mostly the ship was carrying food and cotton.

Unescorted and unarmed, the ship’s master Master Leman Urquhart was concerned about U-boat activity in the area. Hoping to minimize his risk, he sailed closer to the coast than was typical and dimmed his navigation lights as much as possible.

The ruse failed.

On the evening of January 18, Korvettenkapitän Reinhard Hardegen, captain of U123, spotted the navigation lights of the City of Atlanta and began stalking his prey, searching for the perfect shot.

Just after midnight on January 19, Captain Hardegen maneuvered within 800’ of the ship and launched one torpedo striking the City of Atlanta amidship.

The blast was so powerful that it woke people in Kinakeet, now Avon, seven miles away.

The ship immediately began to list violently to port making it impossible to launch lifeboats. One lifeboat may have been launched but according to witnesses it immediately capsized and drifted away.

Making rescue even more unlikely, the torpedo took out the radio shack, and no SOS was ever sent. Captain Urquhart never abandoned his vessel and was last seen helping survivors into the sea.

Abandoning the ship was just the beginning of a night of horror.

The blast from the torpedo spewed wreckage over 850’’—a fact confirmed by U123 that was almost struck by flying debris. Without lifeboats, survivors searched frantically for floating debris.

It seems apparent that lifejackets had been issued and there was little chance that survivors would sink, but the City of Atlanta had been sailing outside the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and ocean water temperatures in January off the Outer Banks are typically between 50 and 60 degrees.

Although there is no accurate count of how many were able to abandon ship, most accounts agree there were more than 20 survivors of the blast. And one by one they succumbed to hyperthermia.

Seven hours later, at 7:55 a.m. when the Seatrain Texas spotted the survivors there were only three still alive—oiler Robert Fennell, second officer Earl Dowdy, and able-bodied seaman Robert Fennell.

The sinking of the City of Atlanta was a shock to Savannah. As the home port of the ship, many of the ship’s crew lived in the city. Flags were lowered to half-mast and services were held for the families of the crew members who died.

Resting in 90’ of water, the City of Atlanta can be reached by experienced divers. However, it’s depth and the water temperature make this a very difficult dive.