The sinking of the Catherine M Monahan doesn’t carry with it the excitement of a daring rescue during a hurricane or nor’easter. It wasn’t sunk by a torpedo or an underwater mine.

Yet the Catherine M Monahan and its cargo may tell as much about the history of the United States as any ship buried beneath the waters of the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

Leaving New York Harbor in August of 1910, the wooden four-masted schooner was bound for Knight’s Key, Florida with a cargo of Portland Cement. Sometime either on the night of August 23 or perhaps during the day of the 24th, the Monahan dragged her bottom along Diamond Shoal and began to take on water.

Just south of Hatteras Inlet Captain J. Sheppard realized the ship could not be saved and he ordered his crew to abandon ship. Signaling the Durant Lifesaving Station at Hatteras that his crew was taking to lifeboats, there was little call for a heroic rescue.

However, Captain Sheppard was so impressed with the professionalism of the Durant Station personnel that he sent a letter to Sumner Kimball the Superintendent of the Lifesaving Service calling attention to the skill and courtesy he and his crew received.

“I wish to inform you of the kind treatment I have had from the men of this station. We abandoned our vessel…in a sinking condition. Signaling us where to land, the lifesaving crew were right on hand to catch hold of our boat and run her up on the beach. In fact, we have had every attention from the keeper and crew of this station,” he wrote.

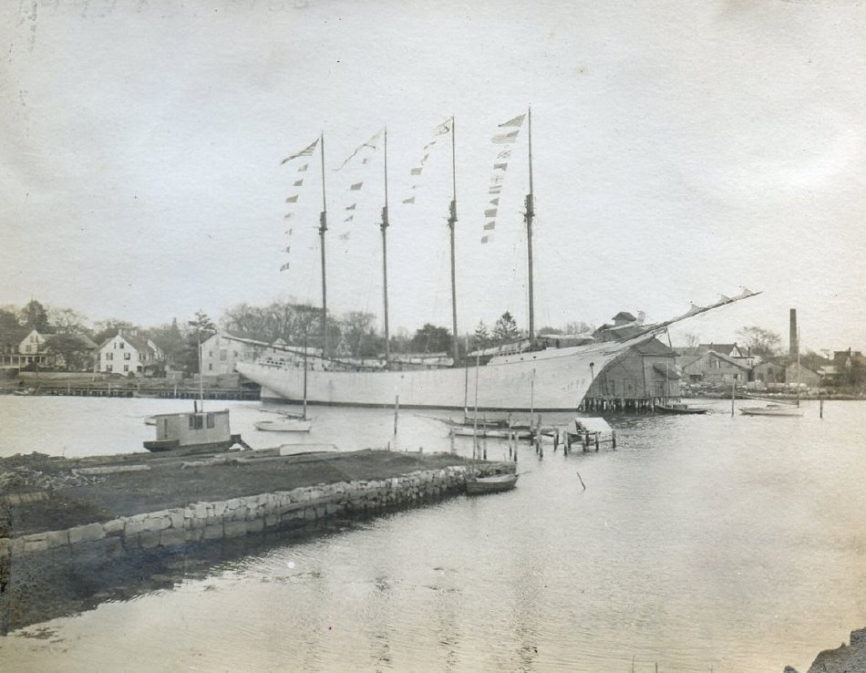

The Monahan was one of the last of a dying breed of ships. Launched just six years earlier in 1904 from Mystic, Connecticut, she was designed to sail the coastal waters of the Atlantic seaboard and had a number of voyages on her log. Although not as large or as fast as the steamships that were already dominating ocean commerce by the beginning of the 20th century, using wind power and only needing a crew of 10-12 sailors, she was very efficient

It is, perhaps, ironic that its cargo of cement was probably destined for one of the most remarkable and innovative engineering feats of its day.

Today there isn’t much at Knight’s Key, Florida. A small Key, really more a part of Marathon Key than a separate island. But in 1910 it was the southern terminus of the Overseas Railroad Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway.

The Overseas Railroad was an ambitious undertaking of Henry Flagler, one of the founders of Standard Oil. Wholly funded by Flagler, his idea was that with the impending opening of the Panama Canal (1914) the deepwater port of Key West would become a commercial and transportation hub for the Caribbean basin.

Flagler had already linked Miami with the rest of the country and had extended his Florida East Coast Railway to Homestead at the northern end of the Keys by 1904.

One year later construction of the extension officially began and by 1908 his the rail line had reached Marathon.

Flagler’s Folly, as many called it, now faced its largest hurdle—50 plus miles of almost open sea to reach Key West.

The project had become a truly international engineering undertaking. Steel beams came from Pennsylvania; for underwater construction, there was a German-produced cement that was ideal; freshwater had to be barged in from Miami because there is no fresh water on the Keys.

The New York produced Portland cement was specifically used for above-water trusses and bridges. Although there is no record saying specifically that the cargo the Monahan was carrying was destined for the project, it’s hard to imagine any other possible use for a shipload of cement at the southern tip of the railroad network at that time.

In 1912, the last stretch of the rail line was completed and Key West was connected by rail with the rest of the country. Many considered the Overseas Extension one of the Eight Wonders of the World of its time.

Because Flagler financed the entire project himself, the exact amount that was spent is unknown. Most estimates put the figure at $50 million, about $1.3 billion in modern dollars.

The extension lasted until the Great Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 which wiped out a number of bridges. Already struggling because it was the height of the Great Depression, the rail line was never rebuilt. However, many of the bridges later became the first roads to Key West before the modern Overseas Highway was finished in the 1980s.

Resting in 100’ of water, the Monahan can be reached by experienced divers. According to reports, there is nothing left of the oak frame of the ship, but the hardened bags of Portland Cement give the shape of the ship and mark its final resting place.