Despite the reputation of the Outer Banks as being in the bullseye for hurricanes, the fact is they don’t come ashore along this stretch of coast all that often. When they do strike, the power and fury of Mother Nature is on full display, but it certainly is not an annual or even biannual event.

Nonetheless, historic hurricanes have ravaged the Outer Banks, perhaps none as horrific as the San Ciriaco Hurricane of 1899.

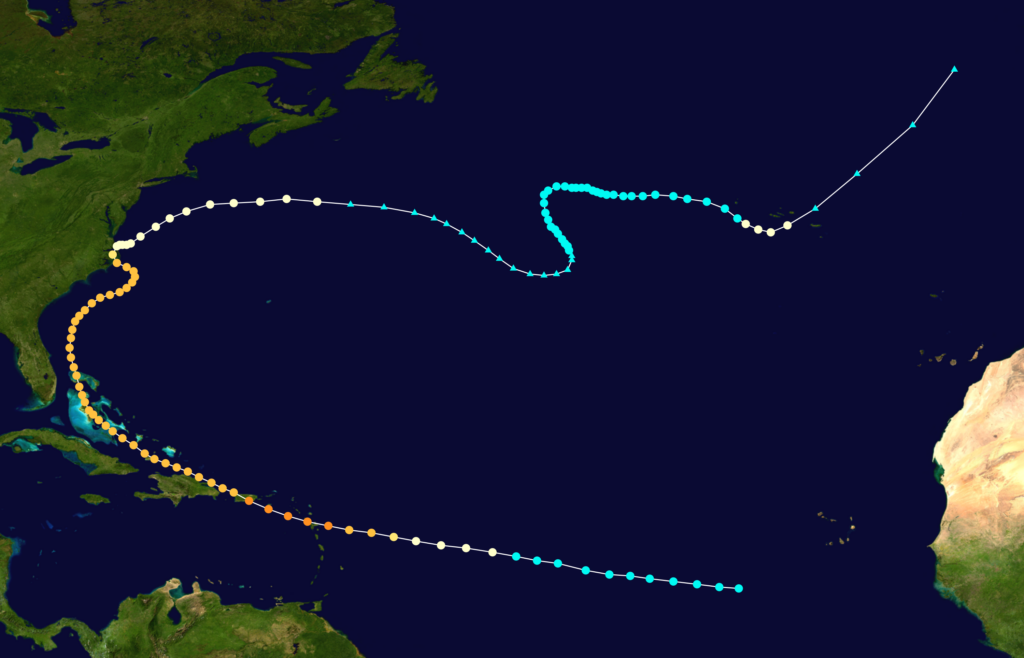

It was first identified as a tropical system on August 3, southwest of Cape Verde. By the time it reached Puerto Rico on August 8, sustained winds of 140 miles per hour were recorded.

The storm turned north, paralleling the southeastern coast, making landfall at Cape Hatteras on August 17. The National Weather Service Station at Hatteras reported sustained winds of 100 miles per hour, with gusts reaching 140. And then “the station’s anemometer was blown away, and no record was made of the storm’s highest winds,” John W. McCain wrote in the September 1941 edition of the US Naval Institute Proceedings.

“The barometric pressure was reported as “near twenty-six inches” (880 MB), which, if accurate, would suggest that the San Ciriaco Hurricane may have reached category five intensity,” McCain went on to write, but added, “Though that’s not likely, it’s understood that this hurricane ranks as one of the most powerful ever seen on the Outer Banks.”

Ocracoke Village was decimated.

“Not since the awful storm of 1846 has Ocracoke been the witness of such scenes. The whole island is a complete wreck,” the Raleigh News and Observer reported on August 22. The 1846 storm was the hurricane that carved out Hatteras and Oregon inlets.

According to news reports, more than 30 homes and a church were destroyed. Another church was moved from its foundation and severely damaged, and ships at dock in Silver Lake sank at their moorings with the loss of two lives.

But it was at sea where the full fury and horror of the storm struck.

The Aaron Reppard was a 459 ton three masted schooner sailing from Philadelphia for Savannah, Georgia with 700 tons of coal. Master of the schooner Captain Wessel was at sea off the Delaware coast on August 13 when the Weather Service issued a warning to mariners to avoid the Eastern seaboard because of the storm. The invention of ship-to-shore radio or telegraph signals was years away, and Wessel knew nothing about the warning.

Wessel’s last chance to avoid disaster came on August 15 as he passed the Virginia Capes and the relative safety of Chesapeake Bay. Still, he chose to sail on, even as the wind grew to gale force, the seas became ever more dangerous, and the ship’s barometer fell.

On August 16, he was sighted by Surfman William G. Midgett, who was patrolling the beach on horseback near New Inlet.

“I sighted her masts through the murk for the first time when she was about a mile and a half off the beach. The schooner was heading north, now making a little headway, then dropping back. She came into the breakers in a few minutes, and I left immediately to notify my station,” Midgett wrote in his official report.

The journey back to the Gull Life-Saving Station, which was two miles away, took him almost 30 minutes as he fought the wind, blowing sand and waves breaking far up the beach.

Gull Station Keeper David Pugh telephoned Little Kinnakeet Station to the south and Chicamacomico Station to the north, asking for help. He immediately put his crew into action, hauling their rescue equipment to where Midgett had seen the Reppard.

The situation was more dire than Midgett’s original report when they arrived.

“The schooner was by this time about 700 yards offshore, stern toward the beach, riding two anchors, but slowly dragging shoreward,” he wrote.

Pugh noted in his report that launching a rescue boat was not possible.

“It was my opinion…that the use of a boat in these conditions was clearly beyond all realm of possibility. No number of men, however skillful, could have launched a boat in those seas,” he wrote.

Two attempts to fire a line using a Lyle gun were unsuccessful, but on the third attempt, the line reached the ship. However, the crew, clinging desperately to the rigging, could not get to it.

The Reppard was breaking up.

There was one passenger aboard the ship—Mr. Cummings—who, according to McCain, was the first to be taken by the sea.

“Cummings, the passenger, aloft in the mizzen shrouds, was caught by one leg in the ratlines and slammed back and forth against the mast until his life was beaten away. Suddenly, the mast fell, and Cummings was not seen again,” he wrote.

The raging sea swept away Captain Wessel and two other crewmen.

There were three crewmen still clinging to the rigging of the ship. One of the crewmen, too weak to hold on any longer, fell into the sea. “A surfman promptly tied a line around his own waist, braved the waves and floating timbers, managed to get hold of the exhausted sailor, and both were pulled ashore,” McCain wrote.

On shore, the Life-saving crews donned cork life vests, attached lines, and swam to the doomed ship, saving the last two crewmen.

The official Life-Saving Service report on the rescue made it clear all that could be done was done.

“There is no doubt that the surfmen did everything humanly possible under the adverse conditions to save the lives of the people on the schooner,” the report found.

San Ciriaco Hurricane Part II

Heroism on Horseback

At least one rescue as the San Ciriaco Hurricane passed the Outer Banks seems more than humanly possible—perhaps because it was a man and a horse that went beyond the call of duty.

The weather was fair with a moderate northwest wind when the barkentine Priscilla left its home port of Baltimore on August 12, bound for Rio de Janeiro. Three days later, the ship was off the Virginia Capes, and although the wind had shifted to the northeast and it was raining, the ship had no problem handling the conditions.

By the morning of the 16th, however, everything was changing. The wind had been increasing all night and was now blowing so hard that by noon, almost all sails were furled. A few hours later, the Priscilla lost its topsail and mainsail as the crew struggled to reef the sails.

Now, at the mercy of a howling gale, Captain Benjamin Springsteen tried to conn the ship under bare masts and avoid Cape Hatteras.

“Of accomplishing that result, however, he must have entertained little, if any, hope,” the official 1900 Life-Saving Service report reads.

Captain Springsteen observed that the water had changed color, and he knew he was no longer in the Gulf Stream. Soundings were getting shallower, and when ten fathoms were reported at 8:00 p.m., “I did not sound anymore. I knew that we were going ashore and passed the word forward for all hands to prepare to save themselves,” the captain told the Life-Saving Service.

A little over an hour later, at 9:10 p.m., the ship was driven onto a sandbar. At first, it may have seemed luck was with the Priscilla. For perhaps 20 minutes, the waves seemed to slip by the grounded ship. But then, the sea began pounding the ship. The crew cut away the port rigging, and three masts went overboard.

Fearing they would be trapped below, the captain ordered all hands on deck.

“The seas were now breaking over the hull with irresistible fury and, in a few moments, Mrs. Springsteen, William Springsteen (the captain’s wife and son), the mate (also the captain’s son), and the ship’s boy, Fitzhugh Lee Goldsborough, were swept overboard, beyond the remotest possibility of aid,” according to the official report.

Also lost was “Elmer…torn from his father’s arms and, somehow, dashed back into the cabin, which was full of water, where his body was subsequently found.”

The ship was breaking apart, and at approximately 4:00 in the morning, “the hull ceased to rise and fall, and the castaways then knew that they must be close to the shore,” although the driving rain, wind, and waves made it impossible to see where they were.

Regardless of conditions, Life-saving personnel were required to patrol the beach, and at 3:00 a.m. Surfman Rasmus S. Midgett of the Outer Banks’s Gull Shoal Station mounted his horse to look for distressed ships. Conditions were horrific.

“The surf was sweeping clear across the narrow strip of sand that separates the ocean from Pamlico Sound, at times reaching to the saddle girths of his horse. The night was so intensely dark that he could scarcely tell where he was going,” is the description in the report.

Less than a mile from the station, “he discovered buckets, barrels, boxes, and other articles coming ashore, which satisfied him that there was a wreck somewhere in the neighborhood.”

Two more miles farther, according to the report, “He thought he detected the sound of voices and, pausing to listen, caught the outcries of the shipwrecked men.”

It was hard to see anything, but peering through the mirk, he made out “a part of a vessel, with the forms of several persons crouching upon it, about 100 yards distant.”

Midgett faced a dilemma, and no matter the choice, death was a very real possibility. It was an hour and a half back to the Gull Shoal Station, meaning the equipment needed for a rescue could not be on site for another three hours. What was left of the Priscilla would not survive that long.

The only other choice was “to undertake to save the lives of the shipwrecked men without aid,” a decision that stood a very real chance of throwing “away his own life, and leave them utterly helpless.”

Evidently, Midgett made his decision quickly, realizing that his only hope of saving the desperate sailors was to save them himself.

According to “The Beach Patrol and a Great Tradition,” a 1944 report on the wreck of the Priscilla, what happened next was truly remarkable.

“With a faithful and obedient mount, he advanced toward the wreck, his horse wading and swimming against the pull of wind, wave, and tide. He advanced close enough to yell instructions for the belabored shipmates to throw themselves one by one into the sea as he proceeded to go out for each of them,” John McCain, the author of the article, wrote.

Captain Springsteen was the first to try his luck, and “Midgett and his unflinching horse plunged forward, reached the struggling Captain, and returned safely to shore just ahead of a huge wall of rising water.”

The process was repeated six more times, but there were three men still on the ship, too weak or injured to jump into the sea.

“To save these men, he must go right down into the sea close to the wreck, take them off, and carry them bodily to the beach,” the official report reads. “Down the steep bank into the very jaws of death three times he descended, and each time dragged away a helpless man and bore him up out of the angry waters to a place of safety.”

Midgett then rode his horse back to the station, and two carts were sent immediately to bring the crew to safety, where “the surfmen quickly took them in hand. They stripped off the victims’ apparel, washed their bodies, gently dressed their wounds, clothed them in dry undergarments, and placed them quietly in comfortable beds.”

For his heroism, Surfman Rasmus S. Midgett was awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal, the highest honor for heroism in the Coast Guard or its predecessor, the Life-saving Service.