There is at the Outer Banks History Center at Roanoke Island Festival Park, a most remarkable book.

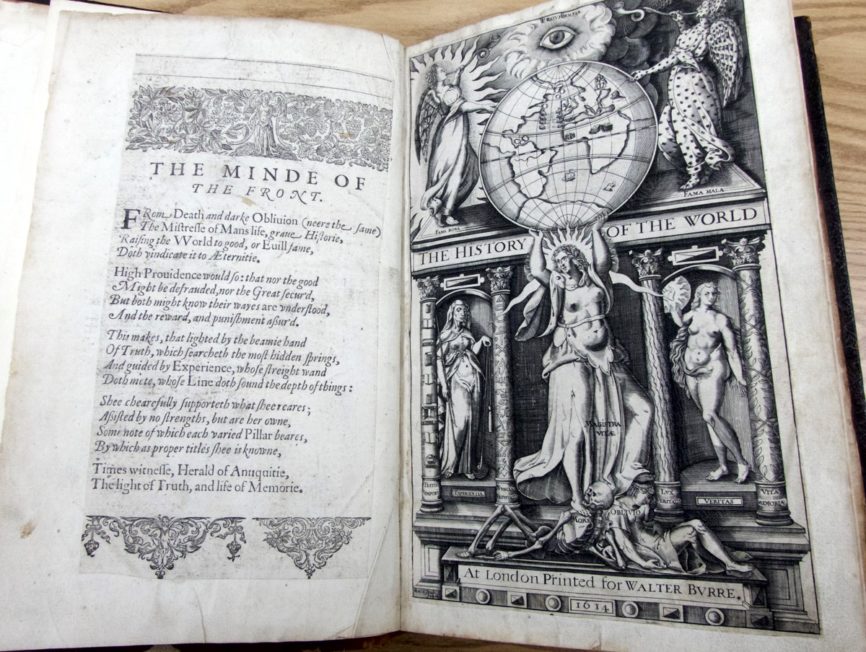

The book is a first edition copy of Sir Walther Raleigh’s “The Historie of the World.”

Published in 1614 the book has been rebound. Stuart Parks, Outer Banks History Center archivist, suspects sometime in the 19th century, although it’s difficult to say exactly when that may have happened.

But the book itself, the pages and printing, are in remarkably good condition. Raleigh’s words are easily read, his style remarkably free of many of the flourishes and endless adjectives of his day.

The book is the property of the Roanoke Island Historical Association, the nonprofit organization that produces “The Lost Colony” play every summer.

How it came to be held in the History Center collection is a little bit unclear. It seems most likely that the book was donated sometime in the 1990s, although exactly when and who donated the book seems a mystery.

Although notes from RIHA board meetings from that period are incomplete, the most likely scenario is that the board was concerned about the ability of the organization to preserve a book that was 400 years old and felt, with justification, that the History Center, with its climate-controlled environment, was in a far better position to handle the book than they were.

Written while imprisoned in the Tower of London, the book is the first volume of what Raleigh intended to be a three volume set beginning at the Biblical creation and ending in contemporary England. Volume One ends at the second Macedonian War that ended in approximately 200 BC.

In many ways, the book highlights how complex and pivotal a character Sir Walter Raleigh was during his lifetime.

To most Americans, he is known for founding the failed City of Raleigh on Roanoke Island—the Lost Colony. And that was certainly one of his greatest efforts and failures.

Yet that venture, as important as it was, does not give the full measure of Raleigh’s life or accomplishments.

Although related to English nobility, his parents were not members of the peerage. He rose to prominence during the Irish War between 1579-1583. Handsome, well-spoken and intelligent, he rapidly rose in the favor of Queen Elizabeth I, becoming one of her courtiers.

The position of courtier was an odd one. It was Raleigh’s responsibility to appear to be passionately in love with Elizabeth, although there could be no physical intimacy between him and his queen.

By all accounts he played the game extremely well, being rewarded by Elizabeth with a knighthood—the “Sir” before his name, huge estates in Ireland and trade privileges, privileges that included monopolies controlling the export of cloth and wines from London.

Although he professed love for Elizabeth I in lines of poetry and as a courtier that was for show. He apparently did fall in love with Elizabeth Throckmorton, one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting. The couple married secretly and his wife was soon pregnant, somehow keeping the pregnancy from the Queen.

When Elizabeth learned of the marriage, she was furious, briefly imprisoning her former lady-in-waiting and, for all intents and purposes banishing Raleigh from her presence.

Raleigh, though, was a member of Parliament and a vocal advocate of a strong British navy and the need for New World colonies to offset the Spanish presence.

As Queen Elizabeth’s death became imminent, he spoke passionately and bitterly in opposition to James V of Scotland coming to the British throne as James I. Elizabeth died in 1603 and within six months Raleigh was accused of treason, in a Spanish plot to assassinate the king and his family.

The charge was without merit—Raleigh hated Spain and was a devout Protestant who distrusted Catholicism. In fact his dislike of James I was rooted in the monarch’s Catholic beliefs and that he was the son of Mary Queen of Scots.

The trial was a sham. Raleigh was not permitted to present evidence and he was convicted and sentenced to death. The king granted him clemency and clapped him in the Tower of London where he wrote the first volume of his “Historie of the World.”

The book was designed as a cautionary manual for James’ son Henry. Not readily apparent to modern readers, scholars agree that the book instructs Henry to be cautious of sycophants and false praise. The book was published in 1614.

Raleigh’s tale did not quite end there.

Believing there was gold to be had in South America, the King released Raleigh from prison so that he could lead an expedition. His instructions were to bring back gold and avoid at all costs Spanish casualties.

Unfortunately, while Raleigh lay ill on one of the expedition’s ships, his son Wat and another ship sailed up the Orinoco River and attacked a Spanish fort. Wat was killed in the attack and Spanish blood was spilled.

Raleigh returned to England, the expedition an utter failure—his son dead, no gold and Spain was demanding his extradition so he could be executed. He was instead once again held at London Tower, convicted of treason and beheaded on October 29, 1616.

That copies of Raleigh’s “Historie of the World” exist is remarkable. James I attempted to suppress its publication and tried to seize all outstanding copies of the book soon after Raleigh’s death, saying the books were “too saucy in the censuring of princes.”