Mid August 1937—excitement was running high on the Outer Banks. President Roosevelt was coming to Manteo for the August 18 birthday of Virginia Dare and a performance of “The Lost Colony.”

Getting FDR to the Outer Banks was a logistical nightmare. There was no good water service to Manteo that could bring the President safely his destination and the roads were primitive, including a two-mile crossing of Albemarle Sound on the wooden Wright Memorial Bridge that was the predecessor to the modern span.

And all of that had to be accomplished with a man crippled by polio who did everything in his power to hide from the public his paralyzed legs.

The halls of power in Washington were not the only place where the complexities of Roosevelt’s trip were under consideration. On the Outer Banks, which at the time was a backwater strip of land with a nascent tourist industry, local officials were facing their own dilemmas. Where would the President eat, how would he be transported, what special accommodation would have to be made for him.

All of those quandaries were questions no one in Dare County had ever faced…but somehow it all worked out.

Roosevelt, it seems, was insistent, and as is often the case, an insistent President gets his way with his staff.

It was finally decided that the only safe way to get him to Manteo was to take a train from Washington, DC to Elizabeth City and have the Coast Guard take him the rest of the way.

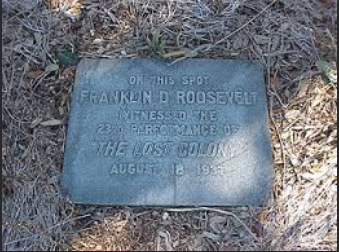

On the Outer Banks, Roosevelt disembarked in Manteo, gave his speech and was whisked off to the Buchanan Cottage in Nags Head, where he ate dinner. He then returned to the Waterside Theater, took in the 23rd performance of The Lost Colony and reembarked on the Coast Guard craft for the return trip to Elizabeth City and home.

There is a question, though, about why he was so determined to make the trip to the Outer Banks. The trip was a logistical nightmare, and although the crowd that gathered in Manteo was huge by local standards, it was insignificant compared to what he would find in any major city. Although Congress was in recess, he had a full legislative agenda he was hoping to accomplish, the open conflict had erupted between China and Japan—he had a lot on his plate.

There were, however, political problems in North Carolina. The governor, Clyde Hoey, was a Democrat, like Roosevelt and gave lip service to supporting the Presidents policies to lift the nation out of the Great Depression. But lip service was all that it was as he and the state legislature thwarted many of the federal government’s programs—usually by refusing to allocate money for matching grants.

His opposition—and that of his predecessor, Governor Ehringhaus who was Hoey’s father-in-law—seemed to spring from their political roots in the manufacturing sector of North Carolina.

Hoey and Ehringhaus were adamantly opposed to any hint of a minimum wage or anything that might drive wages higher. Roosevelt’s policies specifically called for a minimum wage and the funding of the government make-work programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) gave workers an option if they felt wages were inadequate.

The Outer Banks offered the perfect opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of federal programs. To help preserve the small but important tourist industry along the Outer Banks shoreline, the CCC had constructed miles and miles of dunes. Perhaps most importantly, Waterside Theater had been constructed by CCC workers and the production of The Lost Colony was funded through the Federal Theater Project.

The speech he gave in Manteo began innocently enough, talking about the dreams of the “the lower middle classes,” who came to the Americas to find the “…opportunity to get into an environment where there were no classes…”

As the speech progressed, though, he denounced an elitist society where “…malcontents are firmly yet gently restrained…” by these so-called leaders who “…reject the principle of the greater good for the greater number, which is the cornerstone of democratic government.”

He offered instead his vision. “Majority rule must be preserved as the safeguard of both liberty and civilization,” he said, ending his speech by returning to the story of The Lost Colony.

“Those worthy hopes led the father and mother of Virginia Dare and the fathers and mothers from many nations through many centuries to seek new life in the new world,” he said.

Did it change anything in Raleigh? Probably not. The state continued to be difficult to work with but as a footnote to the story of the Outer Banks, it does deserve a chapter of its own.