The Burnside Expedition

An Outer Banks Victory for Union Forces. A brilliant Plan from a Failed General.

The Burnside Expedition is a forgotten slice of Civil War history, although remnants of the campaign still litter the shoreline of the Outer Banks. There is the USS Oriental, its boiler clearly visible about 100 yards offshore just across from the Pea Island Visitors Center.

And then there’s the Pocahontas, lost January 18, 1862, driven ashore in a horrific gale when her engine failed. The remains are there for all to see, the boiler and shaft for the paddlewheel rising above the surface just 75 yards offshore at the end of Sand Street in Salvo.

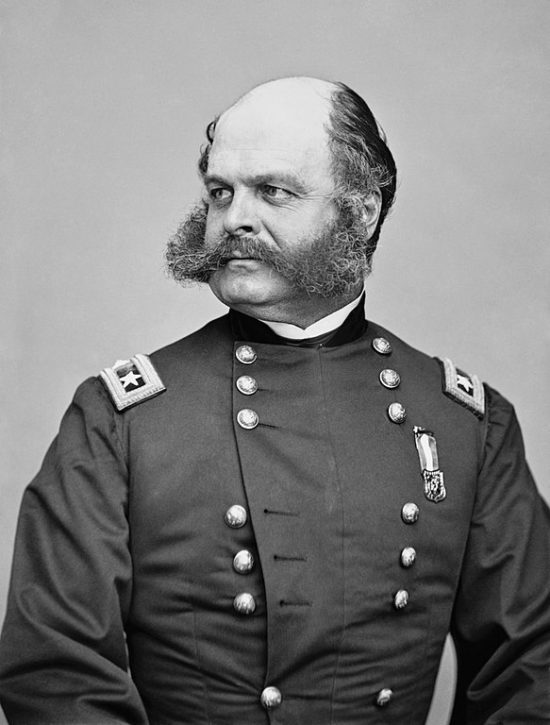

General Ambrose Burnside, who commanded the expedition, went on to abysmal failure later in the war at Antietam and later at Fredericksburg. But in January of 1862, he organized a brilliant military campaign that brought the Outer Banks and all of northeastern North Carolina under Union control.

Burnside himself spoke to the strategy and how he hoped to attain his ends in a lecture to the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Historical Society of Rhode Island in 1880.

“The general details of the plan were briefly as follows: To organize a division of from 12,000 to 15,000 men, mainly from States bordering on the Northern sea-coast…among whom would be found a goodly number of mechanics; and to fit out a fleet of light-draught steamers, sailing vessels, and barges, large enough to transport the division, its armament and supplies, so that it could be rapidly thrown from point on the coast with a view to establishing lodgments on the Southern coast, landing troops, and penetrating into the interior, thereby threatening the lines of transportation in the rear of the main army then concentrating in Virginia, and holding possession of the inland waters on the Atlantic coast, “the transcript reads.

It would be a joint naval and army operation—in itself a radical concept and one that had never been attempted by United State forces before the Burnside expedition.

What the general envisioned was a naval force operating in support of an amphibious landing on Roanoke Island. With Roanoke in Union hands, and naval forces still working with the army, he would then seize Elizabeth City and New Bern.

With Elizabeth City captured, he would be in a position to use the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and Dismal Swamp Canal to open a southern attack on Confederate forces holding the Norfolk area of Virginia.

Perhaps even more importantly, he hoped to use New Bern as a staging area to seize the Wilmington and Weldon rail line, arguably the most important rail line in the South.

The campaign to take Roanoke Island would be the first significant military victory for the Union of the war.

A Fearful Gale As Expedition Gets Underway

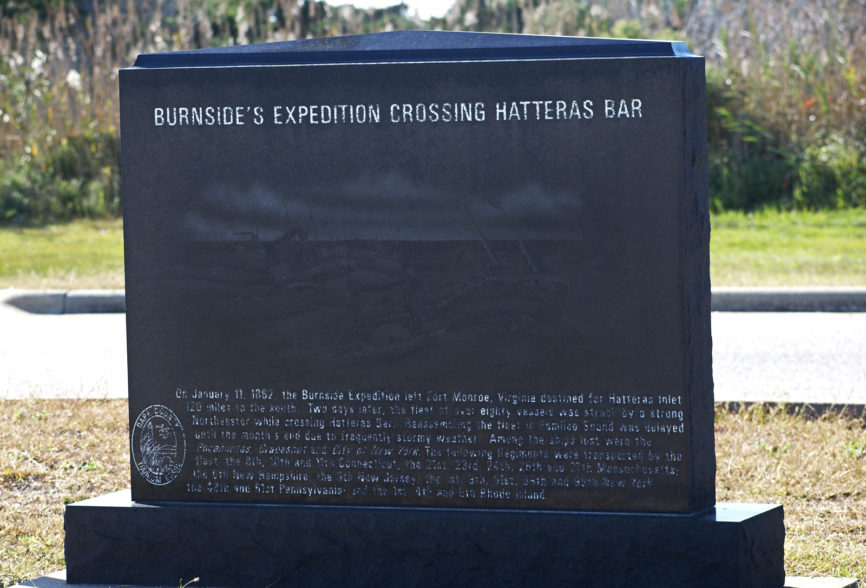

A remarkable hodgepodge of transport vessels and Navy ships left Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia on January 11, 1862.

Dr. Lorenzo Traver told the Soldiers and Sailors Historical of Rhode Island what it was like as the expedition put to sea.

“As the sun was going down, the gunboats, transports, and vessels of all kinds connected with the expedition, could be seen wending their way out of the harbor, in a southerly direction; and in a short time not a vessel could be seen, where only a few hours before a large fleet counted by hundreds,” he recalled.

Things went well at first, but they soon deteriorated.

“During the night everything passed off pleasantly; the sea was quite smooth, with very little breeze, but towards morning the wind began to increase, and by noon it was blowing a fearful gale,” he wrote.

The fearful gale did not let up for days. On Thursday, January 16 the New York Times correspondent assigned to the expedition reported, “Situated between the two extremes of climate, we seem to be in a continual and fruitless effort to find a vacuum…the two extremes of temperature meet, and keep up a, continual contest to see which shall prevail. So we have, one day, a gale from the northeast, and the next day a blow from the southwest; then it pipes from the cold northwest, followed by a lick back from the northeast.” The correspondent is only identified by his initials, E.S.

It was during this storm that the Pocahontas sank. Correspondent E.S. in reporting the incident is blistering in his condemnation.

“During the gale she first blew out some portion of her worthless boiler…The boiler was plugged or patched, and then the steering gear gave way. This was mended, when the smoke-pipe blew down, and as the vessel, from laboring in the sea, had sprung a leak, she was run ashore. The sending to sea of this worthless old bulk, after it was known how utterly unsafe she was with a full deck load of valuable horses and a crew of men, was most inexcusable,” he wrote.

E.S. had more vitriol to hurl at the ship’s crew.

“The teamsters who had charge of the horses were so careful of their own worthless carcasses, that they refused to go down on the lower deck and cut the halters of the animals, thus leaving the poor brutes to perish on the wreck, when they might nearly all have been saved,” he wrote.

Ninety horses were trapped below deck; 24 were able to swim to safety.

The Pocahontas was not the only ship to sink. There was the canal boat Grapeshot, being towed, she began to take on water, and the tow line had to be cut. All men on board were saved.

Even at anchor ships were not safe in the tempest. The gunboat Zouave “dragged her anchors, had a hole stove in her bottom, and sunk. She is a total loss. Her crew and guns were saved,” E.S reported.

Perhaps the most spectacular and noteworthy was the City of New York, a 600 ton screw propeller steamer that was loaded with ammunition and rifles.

Attempting to cross the bar at Hatteras Inlet during the height of the storm proved disastrous.

“It was blowing fearfully, and the whole coast was white with foam, the sea breaking heavily on the bar, and on both sides of the Inlet…Here she was met by a naval steam-tug which…signaled him to follow the tug in. The ship drew 14 feet of water, and no doubt prudence would have dictated that she should have anchored outside for the night,” the Times reported wrote.

The City of New York ran aground. The request for a tow by the tug, refused. The tug “…left the ship in the breakers, without making any attempt to rescue the crew. He did not return, or send any assistance,” the Times reported. It is unclear why assistance was not sent.

The ship remained grounded all night and as the surf pounded the vessel, morning revealed a terrifying scene.

“The violence of the gale prevented any effort to rescue the officers and crew, who remained on board lashed to the bulwarks to keep themselves from being washed off by the sea,” E.S. wrote.

Finally the storm abated and the crew was rescued, although the ship and its cargo were a total loss.

By Friday, January 17, what seems like a classic nor’easter had headed out to sea, and the wind shifted to the South, bringing with it fog and rain. The rain was a mixed blessing. Unable to capture water during the storm earlier in the weak, water supplies for the expedition had become dangerously low. With the southern breeze and calmer conditions, ships were able to capture enough water for the men.

There was another storm a week later and more troubles crossing the bar to the safety of Hatteras, but by the end of January, over 100 ships of every description were gathered and General Burnside was ready to put his grand strategy to the test.

The Burnside Expedition Part Two: The Battle Is Joined – Northern Strategies & Southern Indifference

With the capture of Hatteras Inlet on August 28, 1861, Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside immediately understood the significance of the victory. Two days after seizing Hatteras Inlet he wrote Union military leaders, “The importance of this point cannot be overrated…From it, offensive operations may be made upon the whole coast of North Carolina to the Bogue Inlet, extending many miles inland…”

Hatteras Inlet was perhaps the very first Union victory of the Civil War coming just four months after hostilities began at Fort Sumter in April of 1861, and if Union military leaders understood Hatteras Inlet was a strategic gem, Confederate military leaders seemed oblivious to how vulnerable they were to attack.

Officers on the ground, understood the danger, though. Col. Henry Shaw of Currituck County was in charge of Roanoke Island’s garrisons, taking command in October of 1861. Almost immediately he began lobbying for men, equipment and defensive measures including sinking pilings in the sound so Union ships couldn’t approach the island.

Already stretched thin against a numerically superior Union military, Shaw’s pleas fell on deaf ears.

In late December Shaw sent a memo to Major General Benjamin Huger at Norfolk who had overall command of the northern Outer Banks. The memo details Shaw’s frustration in creating an adequate defense for the island. He had been working up the chain of command, hoping someone would respond to his needs.

“I wrote to Richmond, stating the condition of the defenses…I have never received a reply. My letter was received by the Chief of the Engineer Bureau, who, in a letter dated Dec. 9, stated that my report of the defenses had been received, and would be promptly answered,” he wrote. There is no record of a reply.

When Burnside arrived at Hatteras Inlet, there were 1400 men on Roanoke Island to defend it. They were poorly trained, the equipment was a confusing mixture of military issue and personal weapons—many of them shotguns. The batteries that were supposed to protect the island were not fully armed and in at least one case, had the wrong ammunition on hand. Even if the batteries had been fully armed with the right ammunition, they were located on the northwest side of the island, well away from the approach an invading force would take. There was also a small fleet of ships to support the defenders—the mosquito fleet, consisting of converted tugboats, ferries, and schooners.

Opposing the Confederate forces on Roanoke, General Burnside had 15,000 well-trained and equipped men and 15 gunboats.

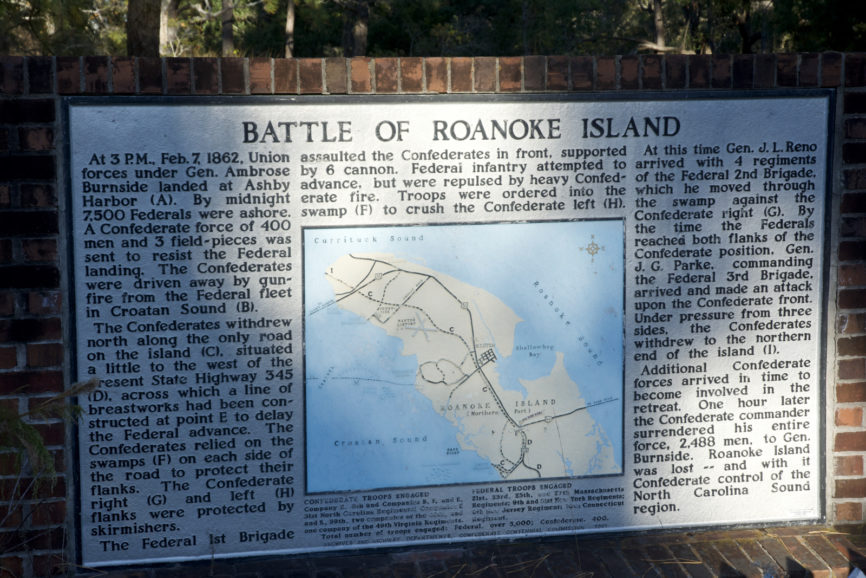

The Battle of Roanoke Island

On February 5 the flotilla of gunboats and army transports left Hatteras for Roanoke Island. Weather slowed their progress and the channel was narrow

The Rebel headquarters for the region was close by at Nags Head, but that was not their target. General Henry Wise, the overall commander for Confederate forces in the area was in the hospital so ill with pleurisy that it was unclear if he would even live. He would survive his illness but he did not participate at all in the battle.

On February 7 at 11:45 a.m. the naval bombardment began. Shore batteries returned fire. The inadequacy of the Southern batteries soon became apparent. Only one of the three could even fire on the northern ships. The mosquito fleet was there as well but had to withdraw after running out of ammunition.

General Wise, in an after action report, was harshly critical of the mosquitos fleet and its commander, Captain William Lynch.

“Captain Lynch was energetic, zealous, and active, but he gave too much consequence entirely to his fleet of gunboats, which hindered transportation of piles, lumber, forage, supplies of all kinds, and of troops, by taking away the steam-tugs and converting them into perfectly imbecile gunboats,” he wrote.

The barrage was intense and went on for some time, yet ultimately very little damage was done. The CSS Curlew was hulled by a shot and the captain ran it aground. Damage to the forts was minimal and the Confederate guns firing solid shot instead of exploding shells, scored some hits on Yankee gunboats but did very little damage.

As the naval battle raged on the north end of the island, Northern troops began landing at 3:00 p.m. at Ashbee Harbor, an indistinct stretch of beach that is today approximately 500 yards south of the Virginia Dare Bridge about at the end of Skyco Road.

As the troops came ashore, a 200-man Rebel force was in place to contest the landing, but they were spotted and Union gunships firing on them chased the threat away.

The landing at Ashbee Harbor was a perfect example of how an amphibious assault is supposed to be organized—with naval gunfire was on hand to suppress Confederate forces attempting to challenge the landing and as a consequence, Burnside was able to move 10,000 men ashore by midnight.

But it was a miserable night. At 11:00 p.m. the wind and rain began, and Burnside, wanting his troops to be able to move quickly, had ordered them to leave tents and baggage behind. Perhaps the most eloquent description of what the night was like comes from the handwritten recollection of Private Chauncey Curtis of the night.

“We bivouacked for a night in a hard cold rain with nothing but our overcoats to shelter us, where we passed one of the most disagreeable nights on record,” he wrote. “Wet and chilled, without fire, we tried to sleep and to be thankful we were on land again. By midnight about 10,000 troops were landed and I guess there could have been but few Christians in that army judging from the vast amount of profanity heard on all sides.”

There was only one road through the island and Colonel Shaw fortified it heavily, reasoning that the marshes on either side of the road were impassable.

On February 8 the battle was joined. A brigade under the command of General John Foster attempted to force their way through the fortifications but were repelled.

Yet as the frontal assault was raging, troops were slogging through the supposedly impenetrable swamp and marsh flanking the road. There was a brief engagement with Rebel forces, then Curtis’ 2nd Brigade under Gen. Jesse L. Reno was ordered to fix bayonets and charge.

“We were ordered to fix bayonets, and the officers were busy getting the men to cease firing…but after a time we were ready and a charge was ordered. Away we went through that slashing, over or under fallen logs as the case might be; through the bushy tops of trees; sometimes in the mud to our knees or running along the top of some log that gave us a few feet of unimpeded progress. Through the lagoon up to our armpits in water; over into the ditch and up over the works, the sand and gravel giving way beneath our feet, and we scratching all the harder; whooping; yelling; howling like demons,” he wrote.

Reno’s brigade and a brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. John G. Parke arrived from opposite sides at the same time, flanking the Rebel forces and leaving them with no escape.

Colonel Shaw, realizing that his position was hopeless, surrendered rather than cause needless bloodshed. His original 1400 man garrison had just been reinforced, but the new troops had arrived so recently that they had yet been deployed. 2500 men surrendered to Union troops.

The cost in blood was relatively light. Northern forces suffered 37 killed and 214 wounded; the South, 23 killed, 58 wounded.

The Aftermath

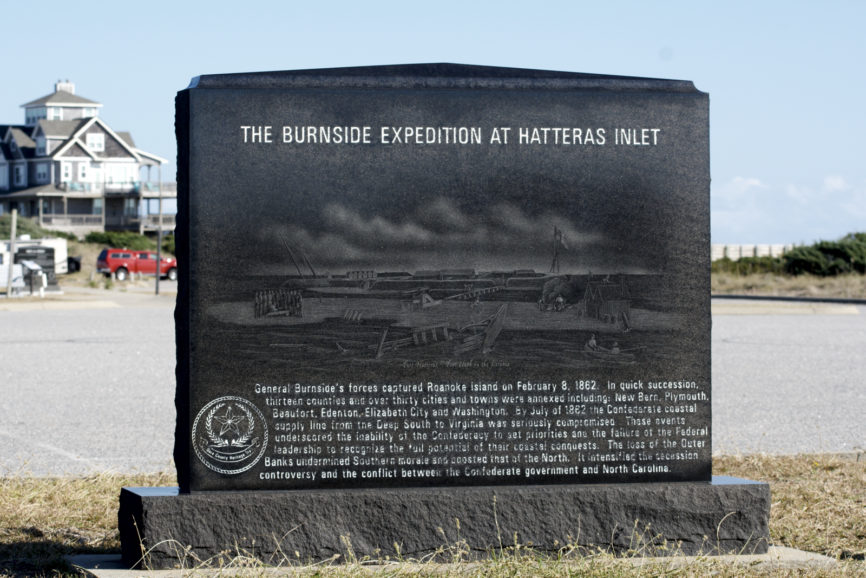

Burnside’s grand strategy was immediately put into effect. On February 10, he seized Elizabeth City; on March 14, he captured the city of New Bern.

His comprehensive plan, however, of severing the supply link of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad and using the Dismal Swamp and Chesapeake and Albemarle Canals to attack the southern flank of Confederate forces in Norfolk never came to pass.

As General of the Army McClellan’s disastrous peninsula campaign unfolded, Burnside’s army was stripped of personnel to stop Lee from taking Hampton, Virginia and Fort Monroe.

Nonetheless, although his grand goal never came to pass, Union forces in northeastern North Carolina did keep Confederate reinforcements from deploying to other areas of battle and for that reason alone may have shortened the war.