Driving along the Bypass or the Beach Road through the main Outer Banks towns of Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills, and Nags Head, it’s hard to imagine that there was a time, 60 or 70 years ago, when the Outer Banks wasn’t really thought of as a tourist destination.

Or drive to Corolla and imagine that NC 12 came to a halt at the north end of Duck, where a manned guardhouse stopped traffic from driving to Corolla without permission. What passed for a road from there to the village of Corolla was a hard-packed dirt and sand road that included beach driving.

For almost 200 years, the Outer Banks was a place to get away from the hustle and bustle of life, but it was reserved for the rich and elite of society only for much of that time.

The history of tourism on the Outer Banks takes place in three eras: the 1830s to the Civil War, the Civil war to WWII, and post WWII to modern times.

The Early Years

In 1830 no one knew what caused malaria, but the best medical advice was that the fetid air of low-lying swamps caused it. With his plantation in Perquimans County, Francis Nixon was desperate to get his family away from the airs he knew would sicken them. In the summer of 1830, he sailed across the Albemarle Sound, coming ashore in Nags Head. Evidently, the breeze from the sea was fresh and clean that day.

Nixon purchased 200 acres at the base of Jockeys Ridge; friends and other plantation owners followed suit, and by 1840 there was a hotel on Roanoke Sound with a boardwalk leading to the beach. A steamship made regular stops at the hotel.

By the Civil War, the hotel, according to reports, could accommodate 200 guests. In 1862 as Union forces consolidated their control over the Hatteras and Roanoke Islands, Confederate General Henry Wise burned the structure to the ground so that it could not be used to house Union forces.

After the Civil War, the Nags Head Hotel was rebuilt, but the migrating sands of Jockeys Ridge proved a greater threat than fire or war. By the end of the 1870s, the hotel was abandoned. Nags Head, however, continued to be a summertime tourist Mecca, with the first of the homes dotting the town’s shoreline. Those homes came to be known as the Unpainted Aristocracy. A number of the homes have survived until today and make up the Nags Head Historic District.

But no one ventured beyond Nags Head. Manteo was not even recognized as a town until about 1890; Kitty Hawk was a smattering of homes ten miles north of Nags Head and inaccessible by road; Kill Devil Hills didn’t even exist.

In 1930 the W.L. Jones Company of Elizabeth City constructed a 3-mile wooden toll bridge across the Albemarle Sound at the location of today’s Wright Memorial Bridge. Five years later, with a newly paved road from Whalebone Junction in Nags Head to the bridge—what is now the Beach Road—the state bought the bridge and removed the toll.

A few homes popped up on the beach in Kitty Hawk and Kill Devil Hills during the 1930s, but Nags Head continued to be what everyone thought of if they even gave the Outer Banks a name.

Post WWII

A number of factors came together to create the Outer Banks as a favorite vacation destination.

A good place to start is with the father and son team of Frank and David Stick.

The Sticks played an outsized role in letting the world know about the Outer Banks. Frank Stick, the father, was one of the most sought-after illustrators of outdoor magazines from about 1910-1930 when he retired from illustrating and moved to the Outer Banks.

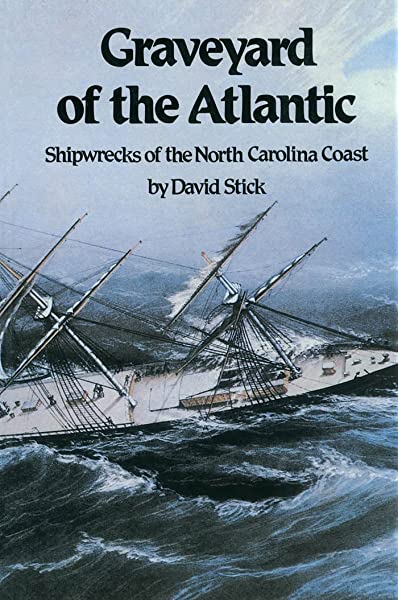

His son, David, is best known as the author of Graveyard of the Atlantic and a number of books on the history of the Outer Banks.

When WWII ended, Frank Stick, the father, came to the conclusion that returning service members would be building families and careers and would want someplace to vacation. So in 1947, he purchased 2600 acres of sand dunes, swamp, and maritime forest north of Kitty Hawk.

Wanting to give his project a warm, welcoming feeling, he called it Southern Shores and began building cement block homes with flat roofs along the beachfront. Those are the flat top homes of the town. At one time, there were well over 100 of them. There are perhaps two dozen left now.

He brought in David to help with marketing, and things really took off. They came up with a plan to sell a lot with a finished flat top home on it for $12,000. That was the 1948 price.

As Southern Shores was being developed, another major event that had been percolating for a while finally came to fruition.

In 1959 Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CNHS) officially came into existence. In 1937 Congress passed an authorizing bill “To provide for the establishment of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore…” But it took 32 years to put all the pieces together. Interestingly, the concept of an Outer Banks national park was first proposed by Frank Stick in 1933, and he remained a passionate advocate for it until it opened.

With CHNS in place and the success of Southern Shores ongoing, development spread to the towns of the Northern Outer Banks.

The notoriety that the Outer Banks was gaining as a vacation paradise was a significant part of what was driving development, but perhaps more importantly, the United States was investing heavily in its transportation system. What was once an arduous 12-hour drive or more from Washington, DC, became an easily managed five or six-hour ride on improved roads.

The stumbling block, though, was that wooden bridge over the Albemarle Sound. In 1962 North Carolina took care of that when the Wright Memorial Bridge opened as a two-lane road. In 1995 a parallel span was added to allow two lanes of traffic in both directions.

The final piece of the puzzle creating the Outer Banks as one place to come and visit was the Bonner Bridge opened in 1963, crossing Oregon Inlet and connecting the Hatteras Island to the rest of the world. The bridge was replaced by the Marc C. Basnight Bridge in 2019.

It did take a while for Corolla to be included as part of the Outer Banks. The village of Corolla had been in existence for some time, and by the 1960s and 70s, there were a few vacation homes there, although not very many.

The problem was, there was no paved road to the village. In fact, the only road was a private dirt road through the Pine Island Hunt Club. There was a guardhouse at what is now Sanderling, and no one was permitted to pass without permission. It was not until 1987 that the state was able to pave the road to Corolla.